An Unreal Publisher: Daniel Scott White from Longshot Press Part 1

An Unreal Publisher: Daniel Scott White from Longshot Press

Part One

By Angelique Fawns

There’s the way everyone else does things, and then there’s Longshot Press. The founder, Daniel Scott White, is forging his own path in the publishing world as “a very independent publisher” seeking work that pushes traditional boundaries.

There’s the way everyone else does things, and then there’s Longshot Press. The founder, Daniel Scott White, is forging his own path in the publishing world as “a very independent publisher” seeking work that pushes traditional boundaries.

His Unfit and Unreal magazines pay an unprecedented industry high of 25 cents per word for speculative short stories.

His imprint also features Longshot Island, a pulp fiction magazine featuring psychological short stories, and Mythaxis Review, presenting articles and interviews looking at books, movies, music, and anything else in the world of art and artists. (I write interviews and articles for Mythaxis Review.)

His imprint also features Longshot Island, a pulp fiction magazine featuring psychological short stories, and Mythaxis Review, presenting articles and interviews looking at books, movies, music, and anything else in the world of art and artists. (I write interviews and articles for Mythaxis Review.)

White has championed writers, artists, and musicians for over 35 years, supporting some exceptional talent along the way such as music legend Bob Dylan, and American scientist/author David Brin whose novel The Postman was adapted into the 1997 film starring Kevin Costner.

After several years of trying, I finally managed to convince this enigmatic and elusive publisher to grant me an interview. There were so many good things to talk about, I’ve divided it into two parts. Our first installment focuses on White’s path to publishing, musical meanderings, and adventures in Alaska. Then stay-tuned for the second installment which takes us to other side of the world in Taiwan, and provides hints and advice for speculative writers.

AF: I’m so happy to finally sit down with you. You’ve helped me immeasurably in my career as a freelance writer, and I’m very interested in hearing about your journey. Where did it all begin?

DSW: I started writing short stories when I was a kid. My mother was into it. She introduced me to the idea of how story submissions worked. I don’t think she published much then. Rejection rates were high, always have been. Later she worked on her novels, but mostly is remembered for her reviews of books. She was a guest speaker on panels at writing conventions in Portland, Oregon. Something about her short story writing shifted over time, though. She started to get pretty good. Some of her later stories really worked.

I used to hide in my closet, as a writer. I had a cardboard box for a desk and a manual typewriter and a lamp. I would sit in there for hours and dream of faraway places. I was only ten years old.

It was difficult, because I had to type every word correctly or the whole page would be wasted. It took all day just to get a paragraph right, hunting for each key, then pausing to consider if I was in the right place on the typewriter. Later, someone explained to me the idea of correction tape. I wrote the stories on paper with pencil, but they looked much better typed up, as if they were professionally written.

The first story I remember submitting went out in the mail, typed, because that’s how we did it then. I sent it to the Alaska Quarterly Review. They wrote back and rejected it, saying it didn’t fit. I hardly understood fit at that time. I hadn’t read anything from the magazine. I just saw their name on a long list and Alaska sounded exciting. The first time I read a short story magazine from cover to cover, I ended up shaking my head. I thought, that’s what they want? Well, I don’t write stuff like that. No wonder they keep rejecting me! Reading the magazine helps, big time.

At an early age my parents took the TV away. I came home from school one day and it was gone. I asked my mom why. She said it was broken. I asked when it would be fixed. She said probably never.

This was something I had brought on myself. I had bad grades, spending my time glued to the TV in place of studying. Instead, my parents gave me a library card. And so, I began reading a book each week, and that grew into 4 books a week. Ironically, my grades continued to stay low as I never spent much time studying, much to my mother’s surprise and disappointment. But she was right, in the end. Books did open my mind. And in time, my grades went up. I turned out alright, in the end.

Somewhere down the road I noticed a lot of my stories were travel stories, although they were fiction. The Hobbit is a travel story, there and back again. The Chronicles of Narnia are travel stories. The Wizard of Oz is a travel story. I also fell in love with travel books, the nonfiction kind. I would read everything I could get in the travel section. Even today, I love to travel, to explore, to find new places and discover new ideas.

A problem I had was coming up with an original story. I thought, if I had an experience, a real, mind-blowing experience, the story would write itself. The world would love it. Then I tried my hand at travel writing.

I rode my bicycle across Alaska. I kept a journal along the way and when I got home, I typed it up. Today, I saw a bear. It chased me down the road, but I still alive. Today, I saw wolves watching me from the tree line. At night I heard them howling outside my campsite under the moon.

Along with travel books, and adventure books, I loved nature books, anything about time spent outdoors. One writer that I really admired was Jon Krakauer, with books such as Into Thin Air about climbing Everest, and Into the Wild, the story of Christopher McCandless. From there I grew interested in the life of Everett Ruess. If you don’t know Ruess, look him up. Read his poetry.

say that i starved, that i was lost and weary

that i was burned and blinded by the desert sun

footsore, thirsty, sick with strange diseases,

lonely and wet and cold, but that i kept my dream!

― Everett Ruess

In Alaska I came across the poetry of Robert Service. There’s nothing like reading poetry in the wild. It is the ultimate experience.

While in Alaska, I sought out the bus called Fairbanks 142, the one Chris McCandless had lived in, near Denali National Park. One day, I found the Stamped Trail and went down it, looking for the place Krakauer had written about. I wanted to experience the location and resources first hand. One thing Krakauer hardly mentioned was the thickness of the mosquitoes in the air in the summertime in Alaska. They were so thick I was inhaling them. As I thought I was getting closer, I looked up and happened to noticed I was hiking down the trail in the wrong direction. Somehow, I had turned myself around without much thought and was moving farther away from the bus. A part of me couldn’t take the mosquitoes any more. I hiked back to where I’d hidden my bike and rode away. That day was a low point, as I had really wanted to find that bus.

Later, I would come across an old man, an army veteran and engineer, living alone in the wild. He invited me to hang out with him, and I spent a week there, seeing first-hand how to survive in the wild, how it was really done. He lived in a bus and had a spare one for me to stay in. His was yellow bus and mine was green. So, in the end, I did get that experience.

When I got home, I tried to write that travel book. I spent five years revising it. Some of the phrasing is beautiful, but no publisher would touch it. The problem was that I planned my adventure too well. Nothing really terrible ever happened, not like you find in a book such as 127 Hours. If I had broken both my legs, and crawled out of the wild, backwards, blinded, while eating moose droppings, then it might have sold. There wasn’t much tension in the story. Where was the antagonist? The wild wasn’t the enemy. It was bliss.

I soon gave up on travel writing. By this time, I had moved to Taiwan, still on the road for adventure. I started writing a column for a company newsletter, telling stories of my life in another country. To my surprise, people read my stuff. I got good feedback. From there, I was asked to write a book for children. It was to be 500 words long. I thought, how hard can that be? It took months to finish. Don’t think because it’s shorter, it’s less important. They go over every word with a microscope.

I went back to school, attending National Taiwan University, earning an MBA degree. I got some of the best grades of my life, graduating near the top of my class. If you think it’s impossible for a guy who craved life in the wild to go back to school and get a master’s degree in business at one the top schools in the world, well, take a look at me. Books did make a difference, in the end. I turned out alright.

After the storybook for children, I continued to work for the publisher, but mostly gaining credits as a consultant on textbooks. About that time, a friend of mine had written a textbook and was looking for a publisher. He thought the book would come across as more legit for schools if there was a publisher behind it. A self-published textbook doesn’t stand much of a chance. As part of my business studies, I had been researching publishers, was considering becoming one. We had an informal arrangement for the book. I bought the ISBN so he’d have one. I put together a website and made a logo for the back cover. He had a school interested in buying it. I think for the first run, we printed 200 copies. The book is still available today. I’ve used it in courses I’ve taught and the students loved it. The method he came up with really works.

AF: Your first career job was in music, including working with some very high-profile musicians. Can you explain that aspect of your life?

DSW: I was born in the mountains, but now live by the sea, as my bio says. In between, I lived on the plains.

I attended Columbia College in Chicago, known for teaching both business and the arts. They had an interesting approach. Most business people don’t understand art, and most artists don’t understand business. So why not teach what’s lacking? Artists there take business classes and business students learn art.

I studied four-part harmonies and audio electronics. I took classes in record company management and recording studio techniques. I studied the inner workings of digital music technology when much of it was new.

The teachers there were exceptional, all of them having experience in the field. It was a rule that teachers there worked part time, to stay current, to stay involved. What we were taught was applied, not theoretical. I learned under Malcolm Chisholm who had worked for Chess Records. He’d recorded Chuck Berry and Frank Sinatra. Two of his songs went into space for aliens to find. I got to meet and talk to Brian Christian who did the orchestration on The Wall of Pink Floyd. And a lot of Alice Cooper records. One of my professors played saxophone on the original recording of Tequila, you know, that song that Pee Wee Herman dances to in his movie.

Then one day I got a job at a recording studio. I’d been told time and again I’d never get a job in the business. A friend from college, Mike Beck, was managing a small Chicago studio known for blues, jazz and folk music, called Acme Recording. He introduced me to the owner, Jim Rasfeld, and I had an interview. It was pretty tense, from my end, although Jim seemed relaxed about it. I was nervous and could hardly talk, but he hired me anyway. I started out making coffee, cleaning toilets, and basically building a whole new studio complex from an old building in need of renovation. Mike later went on to run a highly successful blues magazine, something that always impressed me. Jim and I are still friends today.

I experienced something that I like to call ‘the Before and After effect’. During college, nobody would work with me. I would tell bands, I’ll bring my gear to your rehearsal space, at my expense, even buy you food and drinks. Free of charge. Just let me record your performance. And they’d say no. Not interested. I was nobody.

And then, after getting the job, everything changed. Suddenly, bands were lining up to work with me. I hadn’t become any better at recording from the day before to the day after I was hired. But I was now a professional. I was in demand. It was that fast.

I went on to get enough credits on nationally released album to become a voting member of the Grammy Awards. One of the recording engineers that I was trained under, Blaise Barton, years later would win a Grammy Awards for the Best Traditional Blues Album, called Joined At The Hip.

One particular producer really impressed me, although you’ve probably never heard of him. Michael Frank from Earwig Music Company was a true historian, hoping to record as much blues music in Chicago as he could for later generations to listen to. I think preserving the history of any form of art and culture is important.

Of course, the big moment in my studio work was the time Bob Dylan showed up. That was my 15 minutes of fame.

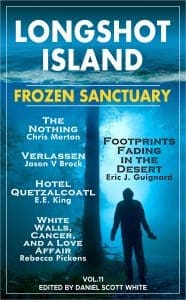

AF: You are mentioned in the Bob Dylan bibliography, Behind the Shades: The 20th Anniversary Edition. How did that come about?

DSW: The sessions were produced by David Bromberg for Columbia Records. David had written songs like “The Holdup” with George Harrison of the Beatles. Later, in 2008, he’d win a Grammy Award. He was a good person to get to know.

DSW: The sessions were produced by David Bromberg for Columbia Records. David had written songs like “The Holdup” with George Harrison of the Beatles. Later, in 2008, he’d win a Grammy Award. He was a good person to get to know.

Blaise Barton was the main engineer and I was the second engineer, which meant I spent my time setting up microphones for Dylan, cleaning his harmonicas and making him coffee. It was a remarkable experience, hanging out with a legend like that. He had a guitar that John Lennon had given him. I stayed after late at night and played that one to an empty room. It had a resonance I haven’t forgotten.

One night, Ringo Starr (another one of the Beatles) was in town, and Dylan’s manager called him up and invited him over to jam. I was stunned by the thought of having two legends at one time in our hole in the wall studio. But Ringo was busy and couldn’t make it.

The full recording, we made wasn’t released. It’s still there, somewhere, in a vault. Two songs were put out and David Bowie gave them a thumbs up in a review. Someday, I’d like to think the rest of the work will come out. Believe me, it’s good stuff.

Many years later, I discovered I was mentioned in a book about Dylan’s life. I’m quoted twice in there. That was a big surprised. I still check from time to time to see if anything new has appeared.

According to the Dylan bibliography, Behind the Shades: The 20th Anniversary Edition by Clinton Heylin (2011), I said, “We worked with the Bromberg band for about three days, wondering if Dylan would show up. Then when he did, there was electricity in the air and they laid down tracks for seven songs in one night.”

And then, down the page, I said: “At times we would get what would sound like the recording of the year. It would be one of those magical musical moments. Then Dylan would say, erase it. I had to record over more than one golden track. At first, I thought he was just teasing us.”

It was really up to the artist to decide what he wanted to keep. And we respected that. We weren’t allowed to make any copies of the music. Dylan is known for having bootlegs made of most of his work. I think I hold the title of being the only person on the planet who actually erased some of Dylan’s best tracks without secretly making copies. They’re gone forever.

The funny thing is that I remember saying those things in the book, but I have no idea how they got there. What more could I wish for? Can’t complain.

AF: Why did you leave the music business?

DSW: The owner of the studio, Jim Rasfeld, sold the business. He moved to LA and worked for Rainbo Records, which is now defunct, doing the layout for CD booklets. I think he liked the change of pace in terms of working for someone else, not having the pressure to keep a business going.

DSW: The owner of the studio, Jim Rasfeld, sold the business. He moved to LA and worked for Rainbo Records, which is now defunct, doing the layout for CD booklets. I think he liked the change of pace in terms of working for someone else, not having the pressure to keep a business going.

The new owners mismanaged the studio. Several months later, we’d lost a lot of clients and I was short on hours. It’s hard to get into the business and also hard to find a job like that at another studio. It’s the kind of work where a hundred people are lined up to take your job if ever you should fail to show up. If you can find enough work on your own, you can bring bands into various studios, but that was a long hill I wasn’t ready to climb.

I took a road trip. I left Chicago and circled the southwest US, seeing a lot of places I’d only read about. Books aren’t everything. Sometimes you have to get out there and experience life. I spent time in the desert, alone. When I returned, I had peace of mind. Whatever the future offered, I was ready for it. When I walked back in the office, I noticed my schedule at the studio was empty. It was time to move on.

Meanwhile, I’d gotten hooked on mountain biking. I moved out west, thinking I was going to enter races. I learned quickly that I wasn’t fast. But I had endurance. Much of society is about speed, right now, right now, but little is said of going the distance.

That eventually led to my bike ride across Alaska.

AF: Expand on how your passion for mountain biking opened the door to your current publishing career.

DSW: Some of my friends had cycled across the country. I wanted to do something similar. I decided Alaska would be the best place for my first attempt. I spent lots of time training before going to Alaska. I’d talked to Ray Jardine, who really turned me on to ultralight travel. Inspired by him, I basically ditched most of the usual camping gear you expect to see people using. The shops in Seattle, they were always pushing you to get the newest gear, the best brands, the most expensive stuff. I went to Alaska without a real tent and found it enjoyable.

For practice, I went hiking into the Olympic Mountains near Seattle and managed to get myself lost for a few days, up above the snowline. Being lost in the wild is an eye-opening experience. I learned something about reading maps that I’d never known before. It doesn’t matter which direction you’re going in. What matter is the change in direction.

It was writing my journal every day that got me more interested in learning how to write well. I think part of the way you become better isn’t by what you write, it’s by the change in direction. You have to figure out what you’re best at writing, and that isn’t always about what you want to do well at. In business, we call that being able to pivot. In time, with success, you’ll enjoy doing what you do best. People need to let go of their preconceived ideas of how their rise in prominence is going to work out. The tools you use when you start at the bottom are different from the tools you’ll need at the top.

The first time I had a short story of mine published, it was through an online magazine, unpaid. I think the story is still there, although the magazine didn’t last long. But I was hooked! I wanted more.

Today I’m convince we need all kinds of magazines, including magazines that don’t pay, like the one my story landed in, and magazines that pay the best of all, like the ones I now run. Imagine a giant funnel. At the narrow end you have the best authors in the world, and at the wide end, the beginners. If we don’t have non-paying magazines, beginners won’t someday become the best in the world. That’s what starts them in the right direction, that initial buzz from when you first get a story published. Thumbs up to the guys who run those kinds of magazines. I salute them.

Please keep your eyes open for Part 2 of Horror Tree’s exclusive interview with Daniel Scott White. Learn how he built his own “empire” of magazines after getting hooked on short story writing.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

Angelique Fawns writes horror, fantasy, kids short stories, and freelance journalism. Her day job is producing promos and after hours she takes care of her farm full of goats, horses, chickens, and her family. She has no idea how she finds time to write. She currently has stories in Ellery Queen, DreamForge Anvil, and Third Flatiron’s Gotta Wear Eclipse Glasses. You can follow her work and get writing tips and submission hints at http://fawns.ca/.

Good interview. Interesting stuff. Thanks.

Thanks, Mr. Wise!