Spooky House Press Author Series: “Frickity Dizzle,” An Interview with Kathleen Palm

Spooky House Press Author Series

“Frickity Dizzle,” An Interview with Kathleen Palm

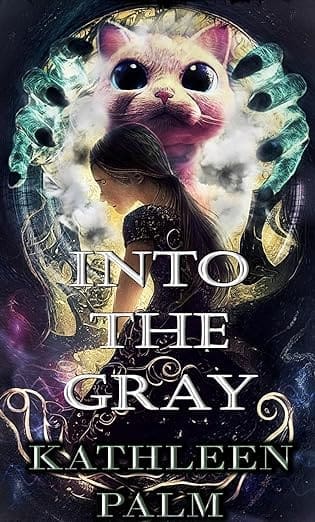

Author of Into the Gray (Middle Grade)

Spooky House Press LLC (February 13, 2023)

By: Jacque Day

INTRODUCTION

As a bonus to the main interview with author Kathleen Palm, we bring you this mini-Q&A with Spooky House Press publisher, Robert P. Ottone, who discusses what distinguishes middle grade from young adult fiction, and why Kathleen Palm’s book, Into the Gray, resonated with him.

Jacque Day: Into the Gray falls into the middle grade (MG) category for readers ages 8 to 12. How differently do you approach MG-rated books versus YA fiction for readers 12 to 18?

Robert P. Ottone: The major key, from what I’ve learned over time, is that middle grade and young adult fiction differ only in the way you present some material. For example, middle grade likely won’t have explicit cursing, sex, or drug use. That said, you can get as bloody or dark with the material as you like.

JD: Why is it important for you, as a publisher, to be open to MG work like Into the Gray?

RPO: My intention wasn’t to specifically find a middle grade book, but when Kathleen’s novel came through, I loved it. It hit every touchstone good middle grade should touch, and most specifically, spoke to the idea that it’s perfectly okay to not be okay. I don’t know any middle grade kids who are perfectly fine. Kathleen taps into that in a meaningful, very real way, and by the way, we’re delighted to have her. Spooky House, as a whole, exists to publish new authors, or newer authors, whatever you want to say, and we’re hoping that Kathleen feels at home and confident in us with projects going forward.

INTERVIEW

And now, the interview with Kathleen Palm, author of Into the Gray.

Jacque Day: Into the Gray is a beautiful novel, and there are so many ways to discuss it: The eerie, instant creep factor of a family moving to a potentially haunted house. The symbolism of color and the lack thereof. Your refreshing, and quite ordinary, portrait of a mixed-race family of two moms and two daughters. The parallel worlds. The central character, Ember’s, brilliant and completely disarming exclamations, like “Frickity dizzle” and “Diddly dang” and “Hecky radical.” We touch on those threads in this interview, though if time and space were no object, I could easily see us devoting an entire discussion to each. If only!

Jacque Day: Into the Gray is a beautiful novel, and there are so many ways to discuss it: The eerie, instant creep factor of a family moving to a potentially haunted house. The symbolism of color and the lack thereof. Your refreshing, and quite ordinary, portrait of a mixed-race family of two moms and two daughters. The parallel worlds. The central character, Ember’s, brilliant and completely disarming exclamations, like “Frickity dizzle” and “Diddly dang” and “Hecky radical.” We touch on those threads in this interview, though if time and space were no object, I could easily see us devoting an entire discussion to each. If only!

To get us started, I’d like to share a fun bit about my reading experience that leads into my first question. I read Into the Gray in a single sitting, lounging on my living-room sofa. After breezing through Chapter 1, I was feeling pretty cozy. At the beginning of Chapter 2, as Ember is wrenched from sleep with a series of thumps, a succession of mysterious thumps rang out in my house. I nearly jumped out of my skin. And this in broad daylight! My first instinct was to run. But Ember, who is twelve, runs toward the thing that goes bump in the night. Why was it important to you, as an author, for Ember to possess this trait?

Kathleen Palm: First, thank you so much for this great opportunity and for reading Into the Gray! Sorry/not sorry that it made you jump!

As people, we tend to run. It’s a self-preservation thing. What if there’s a ghost in the dark basement? Why would we even think of going down the stairs?

However, what if the ghost just wanted to be friends and had cookies? If we don’t go into the creepy basement, or down the tunnel of doom, or follow the ghostly footsteps, we won’t learn anything about what’s there or anything about ourselves. It was important to me that Ember looked into the shadows, chased the ghosts, and wandered into the weird tunnels, so she could grow, change, learn, and eventually accept herself. Ember has a past she’ll probably never know, and, deep down, she hopes she’ll uncover the secrets, but the only way to do that is to go into the dark. Running isn’t always the answer. Hiding might not help. The only way to learn and grow is to face that weird-shaped shadow, to head into the craziness, to go toward the strange, scary sounds. Be brave. Be open. Be yourself.

JD: The setting is so obviously eerie that even Ember appreciates their house as one created for her “horror movie-loving heart.” The Picketts have moved from the familiar, the city they knew, to Gray, a place in the middle of “nowhere” (another major theme in the book) into a house with a tower, where the kids attend the Forgotten Hills School, home of the Banshees, and where a mysterious neighbor girl named Shelly might just be a ghost. Tell me how you went about making the choices that led to the creation of this world.

KP: Writing middle grade books opens up this great opportunity to make stuff up—crazy, weird, cool stuff. ’Cause those fabulous middle graders will jump on that ride with you and have a great time. So I had fun creating the town of Gray, Ember’s house and friends, and Nowhere.

In the brainstorming stage, writing notes and making maps of the town, it took me a while to name the town. I remember sitting on the couch and thinking about being lost, about the gray days of March, and I experienced a lightbulb moment to name the town Gray. A perfect place for Ember to be lost. The school name had to play into that. Since being lost can lead to being forgotten, the school became Forgotten Hills. And the banshees? Because it’s fun and wacky and creepy. I want to cheer for the Banshees.

Ember’s house was easy. I used to walk past this strange, out-of-place house with this odd tower and decided it must be haunted. (I’ve always wanted to live in a haunted house—who hasn’t?) Ember just moved, life is kinda awful, and she needs this hope of getting to live in a haunted house, her creepy-dream-come-true. The house lurks out in the country, with long halls and weird sounds, surrounded by trees and a flock of evil faerie birds, fueling Ember’s desire to chase the shadows and go into the dark. Adding a bit to the mystery of the place, I gave her a very cool neighbor in a white coat, who likes to wander in the middle of the night and loves lost places. This strange, maybe a ghost, neighbor, Shelly, brings some weirdness, well more weirdness, her ability to say what she thinks, and her willingness to believe Ember’s impossible tale.

Because Ember needs someone to tell about Nowhere, the place of lost things. Nowhere was the most fun to create, and it wouldn’t be as awesome as it is without the amazing comments of editor Julie Hutchings. The zombie robots. The little lizard bots. The huge creaking arms that collect all the lost things. The piles of things that have been lost, things waiting to be found again. Caretaker giving instructions and being generally unsettling. And, of course, The Keeper. Nowhere becomes the perfect place for Ember to learn that her search isn’t only about helping her little sister, but healing herself. Horror is a great place to let kids see the fear and doubt and let them wander through it with a friend, like Ember.

JD: One of the most powerful facets of this book is not only the Pickett family dynamic, but your portrayal of the very real and very ordinary problems this family faces. The two mothers, Mama and Mom, have moved the family to Gray for a change. While Mom holds the family together financially, Mama brings a beating heart to the home, but we soon learn that she suffers from depression. The daughters, including the central character, twelve-year-old Ember, and her younger sister, Ash, are adopted, and identify with both their adoptive mothers and their biological mothers. Ash really suffers when her Pink Kitty, given her by her biological mother, goes missing—the inciting incident of the book. Tell me about the choice to place, at the center of your story, a family made up entirely of women and girls. And, what drives Ember to be the protector of her family?

KP: I wanted this family to have depth. Mom and Mama are parents who have their own emotions, care about their kids, but sometimes struggle with life. They’re real people, with real problems, and don’t have it all together. It’s important for kids to see that adults aren’t perfect and, most of the time, are just out there doing their best. Ember and Ash wrestle with a past, one that is part of who they are, but also a past that is lost. I wanted to celebrate a family created out of love, one with questions and doubt, one with a lot of energy and emotions. From Ash’s tantrums to Mama’s depression to the family’s caring for each other, I wanted thoughts and feelings to be front and center, to teach Ember to not be afraid and stop existing in the land of everything-is-fine. I grew up with sisters, and love that connection, and know that if you want to live in a world of pure, out-loud emotion, call in the moms and daughters.

Because Mom and Mama chose Ember, chose to love her, to bring her into their family when her birth mom died, Ember feels incredible attachment and gratitude. In return, she wants to protect them. She would give anything to have been able to save her birth mom, to know her. So she’s going to hold on to Mom and Mama. When Ash was adopted as a scared, lost, little girl, Ember saw a bit of herself and immediately needed to protect her. As someone who loves her family, Ember needs them to be happy.

JD: Throughout the story, color serves as a powerful and multi-layered symbol. The Picketts are a racially diverse family, as is Will’s family. Color-related symbolism also emerges in the sisters’ names, Ember and Ash (also representing phases of combustion), in the name of Pink Kitty and the bracelet that becomes colorful, the town of Gray, the gray itself, the black mist, and in many other instances. Take me into the function of color, and the lack thereof, in Into the Gray.

KP: Having an art degree, color is important to me, even in writing, and not just because of art, because of life. The world is made of color, the people and places, everything, but gray lurks in between. Most of Ember’s story hovers in this gray place, a place of suppressed emotion, a place of waiting, a place of the unknown. But in the gray, she can see the light, the color. Pink Kitty. Ash’s yellow coat. Ember’s rainbow room. Points of hope, reminders of something better, that the gray won’t last forever. But she can see the dark, too. The black fog. The cold. The numb. A place to forget, a place to hide. A place to hold onto bad feelings or ignore what might be best. Ember wanders the gray, dipping her toe into the black, but keeping the colors in sight as she fights to keep her family from falling into depression and loss, to keep them out of the dark. It’s okay to live in the gray now and then, that the light will always be there…but so will the dark.

JD: This leads me to the gray. What is the gray, and why is it important for Ember to go there?

JD: This leads me to the gray. What is the gray, and why is it important for Ember to go there?

KP: The gray. That weird place of being uncertain, of being lost, of being stuck. A place we all end up in sometimes. Being adopted, and her blood relatives a mystery means Ember is always lost with a past that might remain unknown. And now Ember finds herself in a new place with new people and school and everything. She doesn’t know where or how she fits. And even worse, her family is struggling. Ember wants them to be happy again, to laugh, watch movies together, and enjoy muffins on Sunday mornings. Finding her sister’s lost cat has to be the answer, so she searches and insists that everything is fine.

Nowhere, the great place of gray, hears her struggle and calls her to help others heal, to help others move on, so she can, too. Ember wanders the gray, searching for answers she doesn’t know she needs. But answers can’t be found easily, and, while in the gray, she faces the black, the thing that wants her to hold on to her hurt. The gray ends up being the spot where she can see and ponder the light and the dark. She has to go into the gray to face all her emotions, learn what deep feelings linger in her mind and let go. She has to understand that being fine is a lie, that she’s not okay…and that is okay.

JD: Ember’s exclamations are so wacky that they even cause her friends to double-take. When Ember, explaining her name to her new classmates, “wiggles her fingers by her face, as if the introduction needs frickity dizzle pizzaz,” I laughed out loud. Like a side-splitting, tears-down-the-face laugh. This character quirk is a stroke of brilliance. Where did you come up with it?

KP: I’d love to say I thought all those words up myself. But, alas, I diddly darn did not. When I was brainstorming this story…oh so long ago when my daughter was in fifth grade, I happened to hear her group of friends say “frickity dizzle” and “hecky radical.” And those words called to me. Words certainly Ember would use. I asked permission from the group of friends, one in particular who thought them up, to put them in the manuscript. They were very excited that I would put their words in a book, so I received permission and a list of all the phrases. I chose my favorites and used them. In the story, Ember made them up as a means to make Ash laugh, and then they just became part of her vocabulary. I really wanted the characters in the story to react to them, think they’re weird, but in the end, I wanted the characters to accept the weirdness.

It’s been ten years, and sadly the friend group with the hecky radical words have gone their separate ways, so I don’t think the maker of the cool and awesome words even knows that the book with her words became an actual book. Cheers to that group! (Their names appear in the book.)

JD: How long did it take you to write Into the Gray? How long did it take you to sell it? And what was your experience working with Spooky House Press?

KP: Into the Gray has been on a journey. The idea came to me about ten years ago. I wrote YA for years, and it never felt right, so when the idea of Nowhere hit me I knew it was MG. So I began my first MG book.

I wrote this years ago and can’t remember exactly how long it took to draft, but probably around nine to twelve months. The first draft came in at about 85,000 words. Holy moly. Anyway, about four or five years ago, after numerous revision passes and critique partner comments, the story grew and changed and ended up at about 69,000 words. I queried close to one hundred agents, with very little response, so, at the end of that year, I decided to revise it again. With a few added scenes and a lot of deleted scenes, the word count dropped to 57,000.

I had no idea what to do with it. So it sat. But I couldn’t let it go, so I had an editor (the aforementioned Julie Hutchings, who is wonderful!) look at it because I had ripped it apart and put it back together so many times, I worried that it was a frickity dizzle unfixable mess. However, her comments were extremely positive; she said just the right things for me to go back through it and make it pretty much what it is now.

Then I faced the dreaded querying. Still knowing that I had shopped it heavily, I took it slow, found a couple of agents and queried. That time I had a request, along with a rejection. When I saw Spooky House Press tweet that they would be open to submissions for a week, I looked them up and found no middle grade. So, I replied to their tweet asking if they would be open to middle grade. The answer was yes. So I sent in my query and first chapters. A couple of days later I got an email that said they really enjoyed the chapters and wanted the rest of the manuscript. The offer to publish came pretty soon after that. And I jumped on board! Many people aren’t sure with small presses, especially when they want an agent, but I was ready to ride my wave. Robert Ottone is a super nice guy, extremely talented, and the love he had for my little story was clear and wonderful. So I signed with Spooky House and have no regrets. Working with the press has been fantastic! There’s excellent communication, which makes me grateful and happy. I had very few edits (woohoo!). I got to work with the cover designer (shout out to Wayne Fenlon!), who gave me a gorgeous cover. Just an overall great experience.

JD: Into the Gray is a middle grade book for young readers, ages 8 to 12. Does it surprise you that the book resonates so much with adults?

KP: It does not surprise me. As a kid, I wasn’t one to talk about my feelings, more of a push-through-and-it’ll-be-fine type of person. What can I say, I’m a Gen Xer. For me, the message from Into the Gray speaks to my inner child, saying the thing I needed to hear. I think there are many of us out there who need to know that we don’t have to be okay all the time. And learning it now is better than never.

And for parents, this book reminds us that kids see everything. They hear everything. They feel everything. They take it all in, but don’t have the emotional capacity to know what it means or know how to handle all the feelings. Like depression. Like a parent being sick or dying. This book reminds all those parents that a bit of guidance is much appreciated. I believe, like Ember’s Mama, that there is a way to talk to kids of all ages about pretty much everything in an age-appropriate way. And horror is a great way to explore all the scary emotions that wait in the dark and show everyone that there is hope.

JD: Among readers who have reviewed Into the Gray, I find the prevailing takeaway resonating with my own—that it’s okay not to be okay. This is a key theme of the book. Why was it important for you, as an author, to put that message out there?

KP: That is the very thing I always need to hear. So, there must be more people out there who feel the same. Especially for kids, who work so hard to please adults, to do what they’re supposed to, to do everything right, they have to know that when the world crashes down—’cause it will—crumbling, crying, staring at a wall, screaming and yelling…is okay. It’s okay to be upset, angry, sad, that being okay all the time is not possible as a human. The younger we learn this, the better off we will be. You can live in the gray, as long as you remember to look for the light. You can step into the dark. Just remember the light is waiting.

BIOS

Kathleen Palm is a little light, a little dark, and a lot weird. She lives in an old house in Indiana, where she watches horror movies, reads weird and spooky books, and wanders through the haunted cornfields. Her short stories have appeared in Blackberry Blood, A Quaint and Curious Volume of Gothic Tales, and Dark Dead Things: Issue 2. Her upper middle grade horror book, Into The Gray, from Spooky House Press, waits to enchant creepy-loving kids.

Robert P. Ottone, publisher of Spooky House Press, is the Bram Stoker Award®-winning author of The Triangle. His other works include Her Infernal Name & Other Nightmares (an honorable mention in The Best Horror of the Year Vol. 13) as well as the suburban folk horror novel, The Vile Thing We Created.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

Jacque Day writes about stuff she finds too perplexing to figure out any other way. She served as the longtime managing editor for the New Madrid Journal of Contemporary Literature, and has zigged and zagged as a magazine journalist, book and magazine editor, radio correspondent, TV producer, motion picture crew member, and occasional comedy writer and producer. Her newest work appears in the collection, That Darkened Doorstep, published in 2022 by Hellbender Books, an imprint of Sunbury Press.