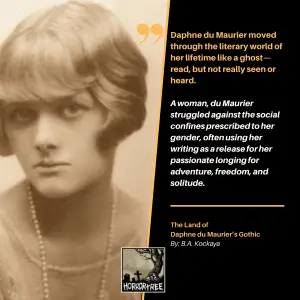

The Land of Daphne du Maurier’s Gothic

The Land of Daphne du Maurier’s Gothic

The Land of Daphne du Maurier’s Gothic

“Writers should be read, but neither seen nor heard.”

Daphne du Maurier

Daphne du Maurier moved through the literary world of her lifetime like a ghost—read, but not really seen or heard. A woman, du Maurier struggled against the social confines prescribed to her gender, often using her writing as a release for her passionate longing for adventure, freedom, and solitude. She championed satisfying work as a source of joy for women; for her, that work was writing, which came before everything else—even her children. In this way, she was revolutionary, and her female characters reflect du Maurier’s own need to break the ties that bound her to a life of socially acceptable domesticity.

Try as she might, du Maurier couldn’t break free of critics’ characterization of her work as simple romance and melodrama; she lamented being “dismissed with a sneer as a best-seller.” Even today, you won’t find her on the Modern Library’s list of the 100 greatest novels published since 1900, despite the fact that Rebecca alone sold nearly 3 million copies between 1938 and 1965, and many readers continue to relegate her to the dusty world of classic lit.

Yet I invite you to consider du Maurier’s work a bit more closely. Nothing in her stories is what it seems to be; nothing and no one can be taken for granted. For lurking beneath familiar people, places, and events is a darker, more sinister world made of deception, anxiety, and psychological terror. Du Maurier’s world is haunted, not only by the supernatural elements that muddle her characters’ understanding of reality, but also by the author’s own ghosts.

That many of her novels, particularly some of the more popular works like Rebecca and My Cousin Rachel, contain both dark romance and literary sensibilities is undeniable; but it is the Gothic which, I believe, most heavily influenced du Maurier’s writing and allowed her to manipulate and innovate with some of the themes, motifs, and elements so crucial to Gothic horror fiction today. In her seminal work Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion, Rosemary Jackson describes the Gothic story as a “topography of enclosures, wastelands, vaults, dark spaces, to express psychic terrors, and primal desires” (64). Though Jackson refers to Poe here, this notion—that landscape expresses mindscape—is nowhere more evident than in du Maurier’s stories.

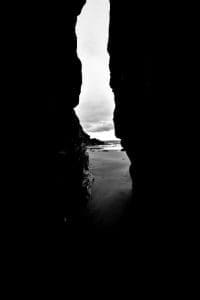

She sets many of her tales in Cornwall, using her beloved landscape to oppress and possess her characters. Manderley, Castle Dor, Jamaica Inn, Bodmin Moor, du Maurier’s Venice: in du Maurier’s hands, each of these spaces becomes a character in its own right, with the power to persecute and terrorize her protagonists, whose states of mind both influence and originate in the landscape. In the dark, windswept countryside of Bodmin Moor stands Jamaica Inn, a monolith not dissimilar to Castle Dracula for the physical presence it impresses not just on the landscape but the lives of the people around it. With painstaking detail, du Maurier draws a map of the moors and, with it, the sinister history that haunts the population and protagonist, Mary Yellan, who becomes enmeshed in her uncle’s obsession—inevitably tied to the moors and his doom. The isolation, loneliness, and fear which attend Jamaica Inn have reduced Aunt Patience to a ghost of the woman Mary once knew, one whose mouth constantly works to form words that seem too afraid to leave her throat. The reader feels that she could use Jamaica Inn as a roadmap to the moor but, if she, like Mary, should choose to walk there, she would find that the paths bring no comfort, no freedom. They trick and entrap, leading only to hidden bogs that suck and drown, or the steep coastal cliffs that cut off any hope of salvation, giving instead the choice between madness, and death. It is only when Mary embraces the ghosts that haunt these spaces that the moors show her an escape route.

She sets many of her tales in Cornwall, using her beloved landscape to oppress and possess her characters. Manderley, Castle Dor, Jamaica Inn, Bodmin Moor, du Maurier’s Venice: in du Maurier’s hands, each of these spaces becomes a character in its own right, with the power to persecute and terrorize her protagonists, whose states of mind both influence and originate in the landscape. In the dark, windswept countryside of Bodmin Moor stands Jamaica Inn, a monolith not dissimilar to Castle Dracula for the physical presence it impresses not just on the landscape but the lives of the people around it. With painstaking detail, du Maurier draws a map of the moors and, with it, the sinister history that haunts the population and protagonist, Mary Yellan, who becomes enmeshed in her uncle’s obsession—inevitably tied to the moors and his doom. The isolation, loneliness, and fear which attend Jamaica Inn have reduced Aunt Patience to a ghost of the woman Mary once knew, one whose mouth constantly works to form words that seem too afraid to leave her throat. The reader feels that she could use Jamaica Inn as a roadmap to the moor but, if she, like Mary, should choose to walk there, she would find that the paths bring no comfort, no freedom. They trick and entrap, leading only to hidden bogs that suck and drown, or the steep coastal cliffs that cut off any hope of salvation, giving instead the choice between madness, and death. It is only when Mary embraces the ghosts that haunt these spaces that the moors show her an escape route.

For du Maurier, darkness is a state of mind, not just a quality of her a novel’s setting. A du Maurier protagonist does not find peace in the daylight: even when the sun shines, an atmosphere of inevitably looms, suffocating, until something—or someone—must break. It is this constantly disturbing, unsettling atmosphere which instills events and behaviors with the sense that they are inescapable: predestined.  “Don’t Look Now” follows the protagonist to Venice and highlights du Maurier’s—and indeed, the Gothic’s—preoccupation with the domestic space. Even abroad, the protagonist cannot escape the trauma that haunts him at home: he brings the oppression with him. On the surface, Venice sparkles with sunshine and happy tourists, its waterways seemingly full of hope and the promise of new life. Yet beneath, where the canals lead to dead ends, the city is dark and twisted. The elderly twins provide a sense of dark foreshadowing and dramatic irony, as these characters, who frighten and disturb the protagonist, ultimately offer him an unaccepted, ignored salvation. The story’s ending contrasts sharply with the atmosphere of joviality and high spirits that surround and torture the protagonist, even as he is unable to experience these himself within the confines of his psychic prison.

“Don’t Look Now” follows the protagonist to Venice and highlights du Maurier’s—and indeed, the Gothic’s—preoccupation with the domestic space. Even abroad, the protagonist cannot escape the trauma that haunts him at home: he brings the oppression with him. On the surface, Venice sparkles with sunshine and happy tourists, its waterways seemingly full of hope and the promise of new life. Yet beneath, where the canals lead to dead ends, the city is dark and twisted. The elderly twins provide a sense of dark foreshadowing and dramatic irony, as these characters, who frighten and disturb the protagonist, ultimately offer him an unaccepted, ignored salvation. The story’s ending contrasts sharply with the atmosphere of joviality and high spirits that surround and torture the protagonist, even as he is unable to experience these himself within the confines of his psychic prison.

While du Maurier enlivens her landscapes to the point that you feel they could reach out and grab you, it is her human characters that ultimately summon the supernatural, imprisoning themselves in their own doomed beliefs and ways of thinking. The namesake of one of her most renowned works, Rebecca, haunts and terrorizes the novel’s nameless protagonist without ever making an appearance. Throughout du Maurier’s narratives, the uncanny prevails, the sense that events and, most importantly, the people participating in them are out of kilter with the rational world. Nothing is what it appears to be. In The House on the Strand, the narrator escapes his bleak married life by consuming an experimental drug that enables him to travel back in time to the 14th century, where he becomes embroiled in the passionate, doomed love affair of Roger and Isolda. The narrator obsesses over Isolda in both the past and the present. When he isn’t traveling back in time to see her, he tries, in his own time, to piece together her story by researching records and ruins and locating the places she used to inhabit. But although the events, people, and places of the novel feel so vivid and real to the narrator, the reader questions his sanity, because the potion only enables him to time travel in his mind, while his body remains in the present. He walks through these visions of the past putting his physical self in danger as his body, unbeknownst to his mind, encounters threats. His consumption of Isolda in the present, his struggle to find bits of her life and the spaces she occupied in a modern, changed landscape, reinforce the narrator’s increasing sense of dislocation and separation from the rational world, adding to the bewildering sense that he is not to be trusted—that he is, as his time traveling suggests, not all there.

While du Maurier enlivens her landscapes to the point that you feel they could reach out and grab you, it is her human characters that ultimately summon the supernatural, imprisoning themselves in their own doomed beliefs and ways of thinking. The namesake of one of her most renowned works, Rebecca, haunts and terrorizes the novel’s nameless protagonist without ever making an appearance. Throughout du Maurier’s narratives, the uncanny prevails, the sense that events and, most importantly, the people participating in them are out of kilter with the rational world. Nothing is what it appears to be. In The House on the Strand, the narrator escapes his bleak married life by consuming an experimental drug that enables him to travel back in time to the 14th century, where he becomes embroiled in the passionate, doomed love affair of Roger and Isolda. The narrator obsesses over Isolda in both the past and the present. When he isn’t traveling back in time to see her, he tries, in his own time, to piece together her story by researching records and ruins and locating the places she used to inhabit. But although the events, people, and places of the novel feel so vivid and real to the narrator, the reader questions his sanity, because the potion only enables him to time travel in his mind, while his body remains in the present. He walks through these visions of the past putting his physical self in danger as his body, unbeknownst to his mind, encounters threats. His consumption of Isolda in the present, his struggle to find bits of her life and the spaces she occupied in a modern, changed landscape, reinforce the narrator’s increasing sense of dislocation and separation from the rational world, adding to the bewildering sense that he is not to be trusted—that he is, as his time traveling suggests, not all there.

Dig a bit deeper into any du Maurier story, and it becomes clear that she excelled at turning traditional Gothic elements on their heads, building on them, changing them, sometimes in so subtle a way that these more complicated strands are eclipsed by other aspects of her work. She brings the horror and psychological trauma of everyday life, situations, and relationships to life in the world we know by “making it strange, without providing any explanation for the strangeness” (Jackson 25), because the world in which she lived was, for her, strange, full of limitations, traumas, and ghosts. Du Maurier imbues the well-worn tropes of her Gothic inheritance with the sense of longing, restlessness, and abjection that permeated her own life. Cornwall provides the backdrop for so many of her works, but du Maurier also uses its landscapes to mirror aspects of her characters’ personalities—and, in turn, her own. The bleak, wild coasts, coves, and cliffs reflect the inevitably of her protagonists’ situations, while creating physical representations of the constraints she felt both as a writer pigeonholed by critics into a single genre, and as a woman unable, due to social strictures, to fully realize the adventurous, radical, loving spirit she felt within her. At the same time, it is this landscape that enabled du Maurier to achieve so much within the Gothic tradition. Du Maurier herself is surrounded by an environment that constrains and dominates her, yet when she embraces the moor and all it represents, she finds true freedom. It is only when the reader loses herself in the land of du Maurier’s Gothic that the shadows haunting that desolate place begin to shine.

References

Jackson, Rosemary. Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion. London: Routledge, 1988.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

B. A. Kockaya writes horror and Gothic stories. She is currently working on her first novel, a feminist retelling of Beowulf with horror elements. Originally from Buffalo, NY, she lives here and there with her husband and son.

You can also follow B.A. on Instagram at @totsbels!