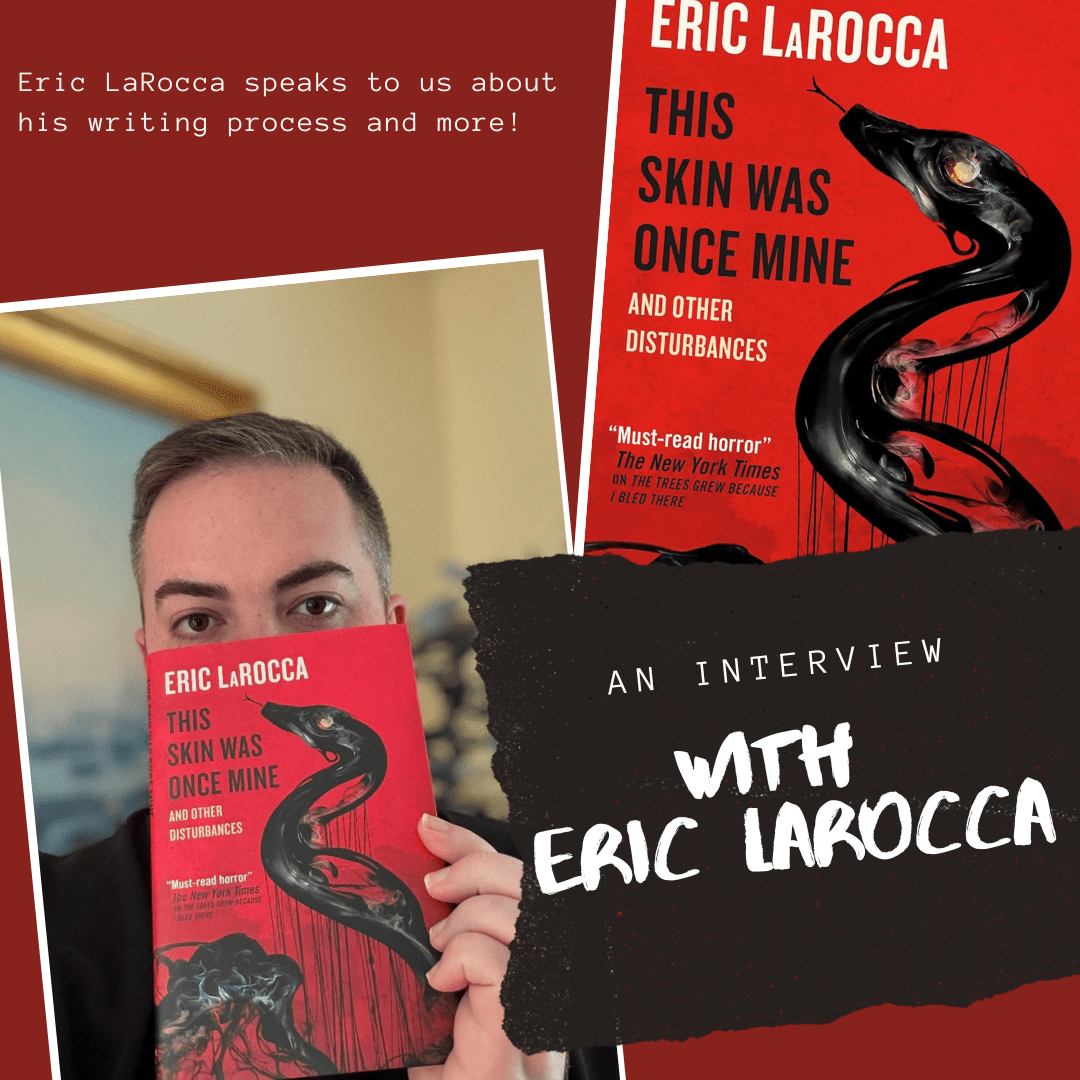

Horror Tree Q&A: Eric LaRocca

An Interview With Eric LaRocca

Eric LaRocca is a 3x Bram Stoker Award® finalist and Splatterpunk Award winner. He was named by Esquire as one of the “Writers Shaping Horror’s Next Golden Age” and praised by Locus as “one of strongest and most unique voices in contemporary horror fiction.” LaRocca’s notable works include Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke, Everything the Darkness Eats, and At Dark, I Become Loathsome. He currently resides in Boston, Massachusetts, with his partner.

PSM: Your work has attracted considerable comment on themes like “transgression” and “body horror” – are there any personal, emotional, philosophical or social drivers at work here?

ERIC: I think I’ve been fascinated by transgression and the human body—specifically, the queer body—from a very early age because I so often felt like I had no autonomy, no voice, as an obviously queer child growing up and discovering themselves inside a very rural, isolated community in Connecticut. My fiction certainly explores the ways in which others mutilate and manipulate the human form. However, most notably, these transgressions are usually sourced from others in the LGBTQ+ community. I’ve always been captivated by the ways in which subcultures form and then consequently implode, disintegrate with certain members devouring others. Although this speaks to a larger issue occurring in the queer community that we probably don’t have time to address here, I think it’s especially unnerving to realize “the call is coming from inside the house.” Not merely inside the animated meat suit we’re each confined to, but also the others existing in our immediate orbit, in our own community. One of the most common forms of advice that younger horror writers are handed is “write what actually frightens you.” I’m truly fearful of only two things in this world: Myself and others. My fiction obsesses over the queer body and the ways it can be influenced, malformed, so much simply because of some of the physical and mental trauma I endured when I was younger, more vulnerable. I believe a great deal of my own identity as a queer person is rooted in trauma, unfortunately. While I might argue that all queerness is entrenched in trauma due to the dangers of our existence in this world, I try not to be so withering and grim simply because I know a lot of younger queer readers encounter my work. I don’t want them to think it’s all doom and gloom. It’s cathartic (although not always completely healing for me) to write about queer transgression in a safe, controlled environment. While I cannot purge myself entirely of the soot attached to my soul, I can perhaps momentarily lessen some of the burden with the sublime act of literary transgression.

PSM: Would you class Clive Barker as a significant influence, and/or who else would you look to as inspirations for your particular take on horror?

ERIC: Oh, yes. Absolutely. Clive Barker has been a major influence on my work since I first discovered him during my time in high school. His fixations on queerness, the human body, the infinite wonders and perils of the human mind seem to overlap quite naturally with my own. I have always been completely beguiled by the uniqueness of his artistic vision. I had never encountered anything before quite like it. Reading Barker’s work also led me to discover other singular literary gems I might not have encountered if I hadn’t connected with his writing. I’m thinking specifically of other equally transgressive authors like Poppy Z. Brite (Billy Martin), Kathe Koja, and Dennis Cooper. I’m very much drawn to writers who have an uncanny ability to blend the bleak and the grotesque with the sumptuous, the poetic.

PSM: What is your perspective on horror as a genre – what if anything differentiates it, what distinguishing strengths it brings to the literary table, what it reflects about wider reality, etc.

ERIC: I think horror is a deeply cathartic and healing genre because of its honesty, because of its intimacy. Horror forces us to confront our fears, our anxieties, our most shameful transgressions in a safe, controlled environment. The genre also affords us the privilege of being as monstrous and vile as we see fit. I realize that there has been a considerable push (especially in online spaces) in recent years for more positive (sanitized) versions of queerness, as if our standing in the real world depended entirely on how we are portrayed in literature. As you can imagine, I am a very strong advocate against the sanitization of queer identities in fiction, especially horror fiction. I think there should be a spectrum of identities represented—from the good natured and kind to the shocking and despicable. Authors (especially queer authors) should be permitted to express themselves freely, to create narratives that suit their vision and to craft characters that are perhaps darker, more complex, maybe even a little “problematic.” Regardless of my interests here, horror really allows us to bare all, to expose our true selves and to allow us the liberty of being as feral, as unhinged as possible.

PSM: Do you have a personal writing process? How do your stories take shape?

ERIC: You know, my writing process varies considerably based on the kind of project I’m working on. I will say that I am a very ritualistic (perhaps even almost superstitious) kind of writer, meaning that I need to complete certain tasks or activities before, during, and after my writing sessions. I won’t go into the exact details of my rituals as they are personal to me; however, I find myself engaging very fluidly with my writing process. Each writing project (novel, novella, short story collection, etc.) unequivocally dictates to me what I need to surrender, what I need to offer to the book in order to create something that I’m proud of. Perhaps I’ll only write at nighttime because that’s what feels right when working on this particular novella. Another project will force me to write only in the afternoon. I allow myself the freedom to be as flexible as I need to be when it comes to my writing. More importantly, I never try to force myself to write or exert myself to the point where it feels uncomfortable or hollow. I sit down at my desk to write almost every day because I am excited to create, to imagine. Not because of any obligation or responsibility I feel. I’m very fortunate to create out of joy and love for the genre, not out of necessity.

PSM: I’m an active member of the BDSM community, and a sometime lecturer on safety and consent. Is knowledge of these types of relationships part of the basis of your fiction?

ERIC: Without delving too deeply into my private life and my sexual inclinations, I have always been fascinated by fetishes and certain expressions of human sexuality. Not simply an aesthetic choice, but rather an emotional and psychological one. My friend, Paul Tremblay, and I have discussed this at length—the importance of writing about your obsessions. Most of my fiction deals heavily with kinks and forbidden fetishes because those are my personal interests, my private passions. I’ve learned a great deal about myself, my true identity, through being so unguarded and I certainly hope that internal growth has bled into my fiction.

PSM: Does the work of Andrew Vachss and similar writers closely involved with issues of abuse, trauma and PTSD have bearing on your fiction?

ERIC: I’m familiar with the work of Andrew Vachss; however, I haven’t read enough of him. This is a perfect reminder. I do often find myself drawn to non-fiction books or memoirs detailing abuse and trauma. In fact, one of the books that really captured and devastated me at a very early age was A Child Called It by Dave Pelzer. I’m sure some readers might find it a clichéd, almost contrived work to reference at this point. However, I recall reading that book when I was thirteen or fourteen in my high school library over the course of several days and being so emotionally drained upon completion. A few very kind fellow horror authors have mentioned to me that my work contains a lot of empathy for my characters. Even the characters who are less than desirable, who might be referred to as “the villain,” for lack of a better word. Although I’m obsessed with creating morally grey, complex characters in horror fiction, I never want to come across as though I’m looking down on my characters or sneering at them. I really strive to preserve a sense of empathy for each character I create even if a reader might label them as “disgusting” or “perverted.” I still need to care about them at the end of the day. I love them and all their monstrousness.