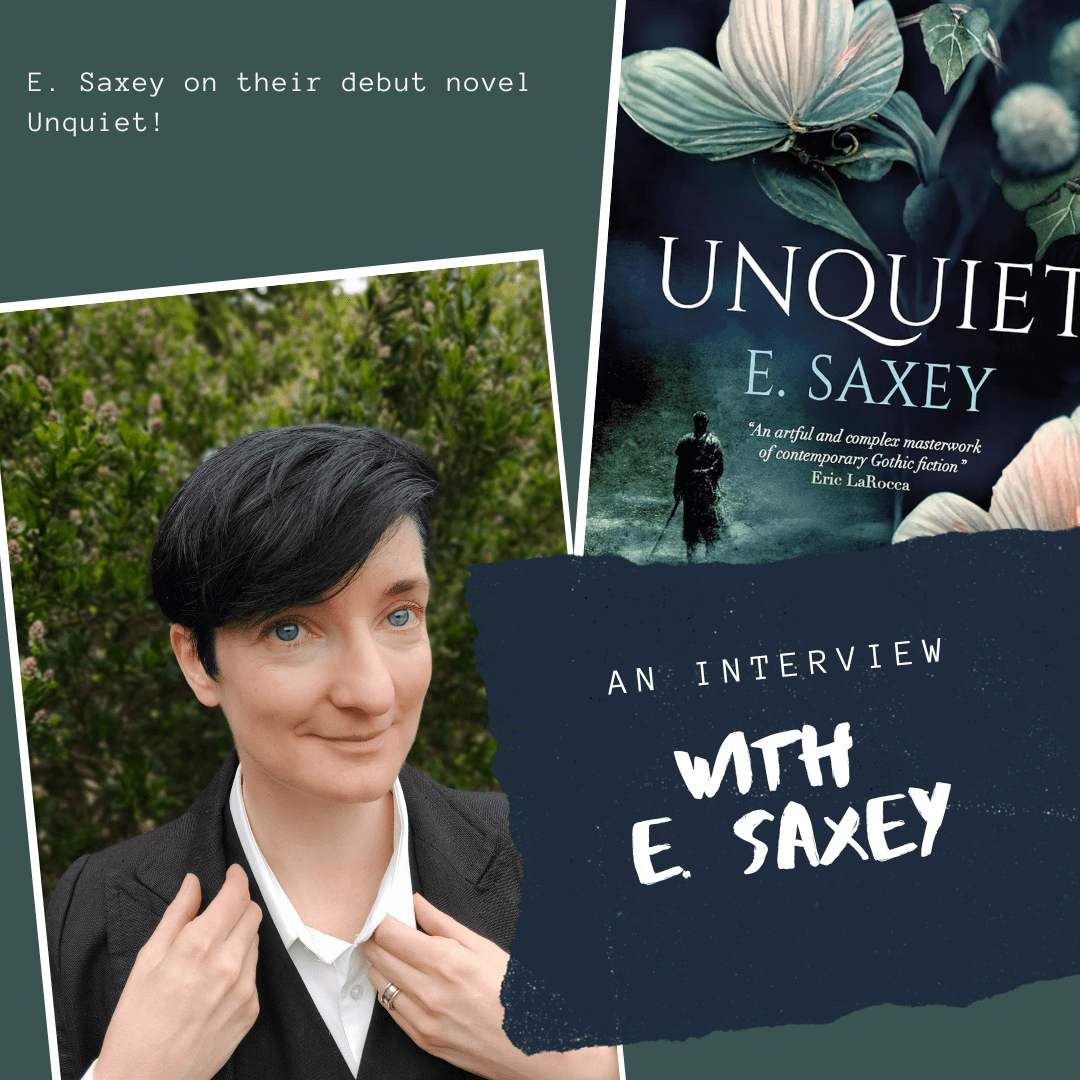

An Interview With Author E. Saxey

E. Saxey is an ungendered Londoner who works in universities. Their fiction has appeared in Daily Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, Queers Destroy Science Fiction and in anthologies including Tales from the Vatican Vaults and The Lowest Heaven. They live in London and tweet at @esaxey.

Firstly, Unquiet is a stunning book. Thank you for sharing it with the world. It already means a great deal to me personally. What do you want people to take away from it?

Ideally I’d like people to find it enchanting and excruciating, a bit of a balance. There are some eerie and agonizing parts, and it would be great haunt readers and generally put them through the ringer, but there’s also art and love and hope.

Having published short stories before, how was the experience of writing and publishing your debut novel?

The editorial attention was brilliant. I know some people chafe at it but I swept through my edits agreeing to nearly everything and thanking my lucky stars that other people were repairing my mistakes. Including classic polite notes on continuity: “The clock has already struck eight in this scene; would you like it to strike nine?”

How has this experience influenced your writing practice, or outlook?

It’s made me fearfully conscious of readers. I’m turning to my work in progress and asking: “Do people want to spend six-plus hours with this narrator? What’s this page for?”. Questions which might put a crimp in the creative spirit, but which are useful for editing.

Victorian London Gothic is a wonderfully rich and enduring favorite genre, even beyond those who typically read genre fiction. What in particular speaks to you about this genre, time and setting?

It’s a time of enormous change and tension. There’s a desire to pin things down – taxonomies, social surveys, folklore histories – and open things up – spiritualism, cheap print, trains, change. Realism and re-enchantment are hand in hand.

What did you want to bring to it that you thought was missing, or thirsting, before? Was there anything old, new, borrowed or blue about your relationship to the world in which Judith’s story unfolds?

I love Neo-Victorian fiction, but there did seem to be a gap. Jewish characters were mostly located in the working-class East End, which makes sense; it’s a remarkable area, and authors can draw on some amazing social histories and fictions. But I’d read novels from the era set on the other side of London, with middle- and upper-class families, and the more I read Neo-Victorian fiction, the more the omission stuck out.

The book is sometimes billed as ‘Gothic Horror’, and horror is often said to address the fears of our time. I found it gently, (un)quietly devastating, as with your other work – lulling, beautiful and ruinous. Do you think this (un)quietness is born of our time? What do you think are the most frightening elements in Unquiet? How do you think Unquiet speaks to the fears of our time, or of Judith’s (or the parallels between both)?

There are layers of fear, for Judith. Some are socially and historically specific, such as her fear of becoming a fallen woman. She doesn’t know what it means, which only makes it harder to avoid. There’s a brilliant non-fiction book, City of Dreadful Delight by Judith Walkowitz, about narratives of sexual danger in London. Judith only gets glimpses of pleasure, and is hedged in by the danger.

Beneath that are some really transcendent fears: loneliness, death, losing others and yourself.

The element of folklore, ritual and symbols is introduced in a way that both invites us in and trusts us to keep up with Judith at her pace. We see rituals both public and private. There’s a sense of tentative ownership on Judith’s part, as if she is dabbling in these as an outsider, attempting to find her footing in practices that she may not be granted permission to engage with by others. What role does folklore play in Judith’s life? And in the story?

I wanted her to have a passion to share with her sister and to carry through into her artistic life. She has a magpie approach. Folklore works for her as an unofficial knowledge, where she doesn’t have to ask permission or get access to a teacher, but can gather up scraps, try things in a creative way, and become an expert. It’s her excuse to roam around London, and even explore the West Country.

It was a double difficulty to work out Judith’s access to the folklore: not only, “Was something happening around that time”, but also, “How would Judith have been able to hear about it?” I consulted nineteenth-century collections of folklore, and found them – as does Judith – frustrating to navigate! But I have Ctrl+F to help me, where she didn’t.

The whole story originated in folk ballads. My favorite folk song is The Unquiet Grave, where a loved one returns after “a twelve-month and a day” of being mourned. Their first words are angry: “Who sits weeping on my grave and will not let me sleep?” That was such an emotional slap – to get your love back, only for them to belittle your grief and confirm that you’ve lost them.

The “twelve-month and a day” of Unquiet Grave made me think of other annual cycles–of mourning, of the seasons–and bring them into contact.

What existing folklore did you draw on in Unquiet, and what was your own invention or adaptation?

I believe all the small-scale tricks and spells Judith tries out, with her sister, are from accounts by contemporary folklorists: things with flames, leaves, rivers and wedding rings.

I then completely invented the two big rituals that take place in the West Country village Judith visits. They were based on traditions such as the Ashmore Filly Loo, which is a cracking midsummer event next to a village pond with antlered men and torchlit dancing (all good stuff).

Also, more modern community festivities like Burning the Clocks at Brighton, a massive midwinter lantern procession ending in a beach bonfire (equally brilliant). I placed my new festivals at midwinter and midsummer, made them both water-related, and thought: What would be enjoyable, or cathartic? What would bring local people together, and bring the reader in?

I feel less guilty for inventing these festivities because even traditional festivals aren’t as unchanging as they can seem; they fall into abeyance and are revived, or are surprisingly recently invented. Up Helly Ah, the Shetland Viking fire festival, was only just old enough to be included in the novel, beginning in the 1880s.

The book has a very strong sense of self – Judith is a beautifully rendered character, as is Sam, through her eyes. How did you weave them together in this liminal journey that could be real, or could be in Judith’s imagination? How did Judith come into being? How much of her character or story is inspired by the writing of Amy Levy, to whom you have dedicated the book (and whose middle name you pay tribute to with Judith)?

The whole book was inspired by Amy Levy. Her novel Reuben Sachs is set in the same community, about five years earlier. Her characters are all struggling in different directions, and she treats them with archness and criticism but also a lot of affection. Levy’s character Judith has some similar challenges to mine; she lives among wealthy families but isn’t as well-off herself, and her options seem pretty limited. My Judith is more miserable and desperate, but she has her art to sustain her (something I borrowed from another Victorian heroine, Estelle by Emily Marion Harris). I wanted Judith to be able to drag herself out of the Gothic fog through her own skill and vision. And both Judiths are plagued by an unreliable and charming man!

Sam was shamelessly based on a friend of a friend, who wasn’t romantically dodgy, but was dazzling and careless and promised people more than he could deliver.

There is also a sense of getting away with something in this story. Judith is, against all odds, mostly left alone, in a time and place where this would not be granted without question. What did it mean to carve out space and solace for Judith in this setting?

I admit it would be hard for Judith to self-isolate so thoroughly. I had to make the circumstances line up: first bereavement, and from it a change of income which makes the family draw inwards, then deliberate trickery. And I wanted to show, around the edges of the plot, her family and friends and community all hoping to hear from her.

For Judith, pushing her family away temporarily looks like freedom. She doesn’t have to cater to her mother, she can focus on her art. But it’s informed by my experience of depression–she’s cut herself off from companionship and support, she has a sense (not unfounded) that there are forces in the city which wish her harm. By the time Sam turns up, she needs company and she’s vulnerable to his manipulation.

It was hard to write her; she keeps making bad decisions, and I had to show they were for half-decent reasons, to keep the reader walking with her. It’s the traditional horror question: why doesn’t she just leave the haunted house? But in this case, it was more like: why doesn’t she let anyone else into the house? Or into her life?

The representation in Unquiet (of women, queerness, Judaism) feels authentic and respectful. What does progressive, intersectional representation look like to you? How do you achieve this in your writing? How do you hope those with, and those without, lived experience of these identities will engage with the book?

When representing a specific experience, I think there’s a big gap between ‘factually not incorrect’ and ‘actually resonating for people’. Aiming at the latter is a patchwork task: I find something from a source, and weld it to a fictional example, hoping the fiction will retain what’s meaningful and communicate it.

This work involved a lot of external input: from primary sources; from fiction of the time, not as a historical record but as an invention with its own aims; and from reader-consultants, who were all excellent.

Thank you for being so generous with your time, talent and knowledge. Where can people find you and your work?

I have a novella available at Giganotosaurus. It’s possibly dark academia, but the darkness is institutional racism and precarious research contracts, alongside the Tudor magicians and immortal monarchs. A lot of short queer weird fiction is in my first collection, Lost in the Archives (Lethe Press). My website is https://thelightningbook.co.uk, and I’m @E.Saxey on X and Bluesky.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts