Magick and Mayhem!

Magick and Mayhem!

Magick and Mayhem!

By

Teel James Glenn

Magick and Mayhem! It conjures up images (yes, its a pun) of cataclysmic tableaus of explosive bursts of light and earth-shaking forces in a battle between warlocks and warriors. But what governs these forces? How is it different from the wave of a wand to make a flower grow or levitate a table? And must they all be grand cataclysmic events, or can simple levitation count?

Drama is, after all, ultimately conflict. It follows then, that as fantasy is a form of drama, it must ultimately involve some sort of fantastic conflict. Like all good drama, however, it must have grounded in characters and principles that a reader can identify with or you lose the connection to the audience and everything becomes just gibberish.

And while that sword fight against the dragon or an orcish boxing match can have a real-world counterpart in a bear hunt or bare knuckles match that can make it somewhat familiar to the reader, Magickal combat must be all the more grounded to make the fantastic believable.

The dictum espoused by Arthur C. Clark that any sufficiently advanced science will appear to be magick and that any magick sufficiently developed will function as a science is never more observed than in writing Magickal combat in a fantasy story. This means that there must be a logical underpinning to any ‘fight’, it can not ‘just happen’ or be described in terms so vague or nonsensical as to veer from fantasy into ‘dream-like’-unless, of course, that is your considered intention.

There is also a parallel rule to be applied: all literature must have self-consistent rules or it loses all drama and becomes a poorly expressed and half-remembered dream as well.

That old Newton’s law of ‘every action has an equal and opposite reaction’ is the commanding principle here. In firing a rifle, this manifests itself as “the kick” of the gun butt against your shoulder as the bullet is expelled from the barrel. Magick should observe this cause-and-effect reality, that I call the ‘ouch factor.’

If you hit someone with a punch you feel the impact of the contact and possibly some of the pain. If you use improper form, in fact, you can be more damaged than the guy you hit! The same must apply to Magickal combat if your system is logically constructed. This could be expressed as the hero/heroine being exhausted, getting sick or some other ‘reflected’ trauma related in someway to whatever spell has been cast.

All this speaks somewhat to the ‘what cost’ issue, a factor that always grounds the story in recognizable reality. Every reader can identify with becoming tired after physical activity or exertion and so it must be with psychic activity.

It is neither good nor bad, just part of the cost of living in the physical/psychic world.

In the great fantasy epic ‘Lord of the Rings’, J.R.R. Tolkien was particularly aware of establishing ‘real world’ criteria of rules for the magic/k used. He was very much aware of the “Magick-has-a-cost’ principle, indeed, the quadrology (counting The Hobbit) is ultimately about that. The price that Bilbo/Frodo pays for the power of The Ring is almost life destroying.

This is always a humanizing factor in stories of great power; what must the protagonist give/lose/risk to exercise their power? What is the limit of that power? What is its source? As well as an allegory of addiction and the corruption of power, the books are a fantasy version of the laws of physics as regards to energy use.

Not all magick, of course, will function under the same laws or rules, like the laws of physics, in different stories.

The rules governing magick must, however, be carefully drawn and consistently followed in each world/story an author explores. And the reader needs to be in on the rules (to some extent) or the whole thing becomes an exercise in “God Machine” writing and the reader will lose interest.

You can’t just pull out a brand-new rule to save a hero if you have not set it up early. Very much the principle of ‘if you bring a gun on stage in act one you have to shoot it before the end. The corollary is that if you want to suddenly have that gun you have to at least imply it early in the tale.

No one understood this more than the exceptional writer Randall Garret in his Lord D’Arcy stories. In them he postulated a world where 1) Martin Luther’s edicts were listened to and there was an internal reformation in the Roman Catholic Church, 2) Richard the Lionhearted did not die in France, but rather returned, kicked his brother John off the throne and thus the Plantagenet line still ruled the Anglo-French empire in the 1960s and 3) the Rules of Magick were discovered, recognized and codified by the Roman Church.

In this world Lord D’Arcy is the chief investigator for the Empire in dealing with crimes by or against the nobility and his chief assistant, Master Sean O’Laughlin, is Chief Forensic sorcerer—a church sanctioned government post. A one-man Magickal crime lab!

The series was a wonderful combination of Sherlock Holmes and Merlin that broke the here-to-for held belief that you could not mix magick and mystery in a deductive story, because it was felt that the introduction of Magick into the mix made playing fair with the audience impossible. Garret made sure that the clues to the solutions of the Lord D’Arcy mysteries were clearly set out and whether empirical or Magickal always made sense. It did it so well that the master wordsmith, Garret, got an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America.

Within this world of magick/science Garret made sure the physical laws and Magickal laws were clearly laid out, consistent and compatible. He took particular delight in asserting that the laws of optics not be discarded in creating such things as invincible capes or swords (in sharp contrast to Tolkien who chose to ignore that law within the context of his differently, but brilliantly conceived Middle Earth).

In Lord D’Arcy’s world, rather than actually rendering those objects invisible, Garret has them ‘spelled’ with a spell of aversion so that no one can directly look at the wearer of the cloak. This effectively renders them ‘invisible’ even in a crowd.

The sword, thus ‘spelled’ was almost impossible for other swordsmen to fight until the hero concentrated on ‘feeling the blade’ and looking away, thereby seeing it occasionally in peripheral vision. This left them vulnerable to casting reflections and leaving tracks in snow or soft earth. All logical and well thought out.

This brings up an important point in magick based combat systems: vulnerability. Or the ‘Superman’ dilemma’ as some have termed it. You have to be careful to build in a natural weakness in your magick system as the creators of the Man of Steel discovered by the mid-forties when they realized there was no suspense anymore with a hero who’s sneeze could snuff out suns so they ‘retro fitted’ him with a weakness in Kryptonite—irradiated chucks of his home planet that robbed him of his powers. This proved so useful in providing plotlines that the writers began inventing a rainbow of meteor chunks to keep things fresh.

The Creators of the Golden Age Green Lantern, with his magick ring that materialized his every whim were smart enough to give him a weakness from the beginning, one whose very mundane nature was a great contrast to the fantastic ness of the ring. The ring’s weakness was an inability to affect any object made of wood!

When Gardener Fox reimagined the character with a science-based ring, he built in the flaw that it would not work on anything but the color yellow. I know that seems an arbitrary weakness, but in a primary color comic book such imagery was powerful.

Now we have “what cost’ and ‘what weakness’ to the magick system so add to that a ‘what means.’ that is by what mechanism is the magick accomplished.

By that I don’t mean magick wand, magick staff, or magick Spork I mean the principles beneath.

Every Magick system should have an underlying structure that defines its strengths and weaknesses even if these rules are not disclosed to the readers in total. It is essentially the same as having a solid ground plan for a building plotted with space for rooms not yet constructed; the actor’s equivalent of doing a character biography for their role in a play even if it is a minor one.

For my Altiva fantasy series (The first one out now from Airship27 Press ‘Dragnthroat’) I developed three parallel magick systems: (space) warps, crystal craft, and priest voice.

The first is fairly self-explanatory: spatial anomalies that exist or are summoned in this art practiced by the mysterious warp wizards. It utilizes naturally occurring or specifically created warps that are evoked, modified or ended by using the harmonic commands of ‘wizard tongue’, a dead language learned only by the warp mages.

The crystal craft is practiced by crystal smiths who grow objects to specific shape and size in chemical baths. Such things as ‘fresh bowls’ in which any object is kept at undecaying perfection or specific charms that enhance a voice, one’s hearing, or sense of smell. Another aspect of the crystal craft and an important one on the medieval level world of Altiva are growing crystal blades, weapons grown in the owner’s own blood and thus attuned to them. The weapons are so in tuned, in fact, that when the owner dies the blade shatters and, so legend has it, if the blade breaks the owner dies!

The third magick is ‘voice’ magick by which priest singers of the Kova religion can heal or hurt. The priests train to be able to use their vocal chords independently to produce multiple tones, which can do remarkable things, some of which are preternatural. This has a hint of the Hindu/Vedic concept of mantra’s raising one’s vibratory rate but was not, I confess, originally a conscious analogy.

The thing about the three systems is that, though not apparent in the stories, all three are actually one system. Based on the principles of physics and the science of harmonics, the multiple systems fit into a template of ‘possibles’ and ‘impossibles’ that are clearly defined in my plans for the world with built in weaknesses, strengths and peculiarities.

Lest you think all this is purely the realm of the fantastic take note that there are real-world counterpoints to these Magickal principles. Some of the same factors in the real-world combat systems of China’s Tai Chi Chuan, Korea’s Hwa Rang Do, and Japan’s Ninjitsu and Aikido reflect the three “Whats” in their underlying principles: What cost? What weakness? and What means? These arts utilize Chi/Ki, which, like the ‘Force’ of George Lucas’ Star Wars ‘magick’ system, is the life energy in all things that connects all matter. These arts use Ki/chi as an intimate part of the combat strategy.

Each in their own way seeks to tap into the Ki of the opponent and use it against them. All four draw ‘power’ from stance, breathing, meditation and (to a greater or lesser degree) diet to maximize the practitioner’s ability. Much is made of this connection between mechanical and ‘energy’ strength in the four arts mentioned.

They each recognize that there is a cost for the damage they inflict. On a purely biomechanical level, they emphasize stance, targeting and focusing to minimize the ‘blowback’ effect of striking an opponent.

Something as simple as a bent wrist can cripple the attacker themselves and small bones meeting big (i.e., fist to head) can be disastrous. They also (and this is why I refer to them specifically) recognize a ‘psychic/moral’ cost.

In fact, all three require their higher practitioners to study the healing arts as a way to offset the violence that they may do. Each warrior may more fully comprehend the consequence of his or her actions with this knowledge. This helps them also see the weakness and strength of their own art.

Tai Chi (either Chen or Chuan family styles) is perceived by many here in the states as a slow-motion exercise that old people do in the park. And that is one part of it, but it has been proven to increase blood circulation, lower blood pressure, and increase lung capacity by western science.

It is also a very deadly martial art that uses the energy of the attacker against him. There are stories of Tai Chi masters being able to break swords with apparently gentle taps against the blade and killing with the “Dim Mak” a delayed deathblow that is made as a feather-light touch as one passes the victim in a crowd. It is rumored to send ‘Bad Chi’ into the body of the victim and kill them days or weeks later from internal bleeding. This may have a basis in real-world biomechanics with a carefully placed and apparently gentle blow to the kidney area inducing internal bleeding that would have been undetectable and unstoppable in medieval China.

All four of the arts are more then biomechanical at their higher levels. Hwa Rang Do (which means Flower of Youth) is an eighteen-hundred-year-old art from the mountains of Korea that was founded by a Buddhist monk as a way to hone the youth of the Silla kingdom to the highest levels of physical and spiritual perfection. It is an art I have been privileged to study. A practiconer at the higher levels is expected to utilize ‘mind control, invisibility, and other ‘super normal’ abilities in a part of the inner art which is called ‘Shin Gong.’

The student of Hwa Rang Do is able to influence the minds of others when this ability is fully learned. A guard, for instance, can be made to look the other way or be made sleepy at the right moment for a spy to infiltrate some building undetected. (This part of Shin Gong is called chuem yan sul.)

Ninjitstu, the Japanese ‘spy art’ which owes something to the Korean and Chinese ‘stealth scrolls’ of the Chinese military genius Tzun Tzu (author of the Art of War) though developed its own unique practices has similar ‘mind influencing’ techniques at its higher levels for exactly the same purpose.

I have personally seen attackers unable to move and myself have been paralyzed by the seemingly impossible mind control techniques of my master. He ascribed my inability to react to Shin Gong with a knowing smile and I have no reason to doubt him.

I’ve also experienced the other side of it as “going between breaths” while performing the art of Iaido—the quick drawing and resheathing art of Japan. Only twice, and I am sad to admit it, I am not quite sure how I got there.

I have, through focused thought, been able to draw and cut my partner while he remained unable to respond—between his breaths—and yet I did it with no great speed. Whether it was through some primordial body language, hypnosis, or telepathic connection, I cannot say.

Magic/k? Maybe. And if so, it would have to function under some set of natural laws. Therein lies the real story here, but remember that magick must be treated as a ‘natural force’ in any world where it is used, subject to the laws and rules of that world, but while it and Magickal combat may thus be ‘scientifically’ treated, it is up to the writer to make it Magickal for we, the readers to enjoy!

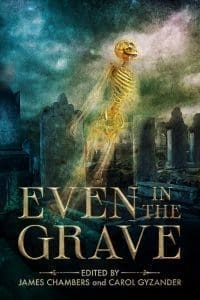

About Even in the Grave, edited by James Chambers and Carol Gyzander

About Even in the Grave, edited by James Chambers and Carol Gyzander

“In death – no! even in the grave all is not lost.” –Edgar Allan Poe

Wandering souls! Restless spirits! The vengeful dead! Those who die with unfinished business haunt the living and make their presence known from the world beyond:

A scientist’s invention opens a window onto a terrible afterlife.

A New York City apartment holds the secrets of the dead.

A grandmother sends text messages from the grave.

A samurai returns to his devastated home for a final showdown with his past.

A forgotten TV game show haunts a man with a dark secret.

A tapping from behind classroom walls leads to a horrible discovery.

The specter of a prehistoric beast returns to a modern-day ranch. And the one seeing eye knows all—including what you did. Haunted from the other side, these stories roam from modern cities to the shadowed moors to feudal Japan to the jungles of Central America, each providing a spine-chilling glimpse into the shadows not even death can restrain. Do you dare open these pages and peer into the darkness they reveal?

Stories by Marc L. Abbott, Meghan Arcuri, Oliver Baer, Alp Beck, Allan Burd, John P. Collins, Randee Dawn, Trevor Firetog, Caroline Flarity, Patrick Freivald, Teel James Glenn, Amy Grech, April Grey, Jonathan Lees, Gordon Linzner, Robert Masterson, Robert P. Ottone, Rick Poldark, Lou Rera, and Steven Van Patten.

Available at eSpecBooks