WIHM: An Exploration of Menstruation in Horror and Dark Fiction

By Tabatha Wood

“Shark Week.”

“Aunt Flo’s here.”

“Riding the Crimson Wave.”

There are over 5,000 different slang terms and euphemisms for menstruation, according to an international survey conducted by the people behind period-tracking app, Clue. With over 90,000 people across 190 countries adding to the list, the type of phrases range from the obvious to the ridiculous. And yet, it begs the question: what is it about menstruation that makes some people feel like even the word itself is dirty? That many women feel unable or ashamed to say, “I’m on my period.”

It stands to reason that there will be a woman — or someone of another gender — reading this piece right now who “has the painters in.” The onset of puberty heralds “Mother Nature’s” arrival, and barring illness, pregnancy, some medication or use of certain contraceptives, this monthly visitor brings her scarlet luggage with her up until the time of menopause. The loss of blood is considered emblematic of a young girl’s entry into womanhood. No longer a child, immune from the Male Gaze, but a fertile vessel, sexual, and capable of bringing forth new life. It is a normal and expected part of most cis women’s lives. Except it is rarely talked about unless in hushed tones, and hardly ever in places where men might overhear. It is only very recently, for example, that televised adverts for menstrual products have replaced the colour of the liquid symbolising blood loss from unnatural blue to a more accurate red.

Does horror fiction perpetuate this shame and discomfort, or can writers seek to remove any stigma by normalising menstruation in text and film? You might think that in a genre which delights in exploring themes of the bloody and disturbing, there may be more than a handful of examples that also include menstrual blood. But it appears that the “monthly curse” is often too terrifying a concept, even for horror writers to exploit.

Probably the most famous example of menstruation in a dark fiction novel is in “Carrie” (1974) the debut novel of horror heavyweight Stephen King. A motion picture based on the book was released in 1976, directed by Brian De Palma, and was the first time menstrual blood was depicted on screen.

The eponymous Carrie is a teenaged girl with a background of sustained abuse, both from her peers and her zealot mother. She gets her first period in her high-school shower room, and with it comes a dangerous ability.

“Plug it up!” her classmates yell, as they pelt her merciless with sanitary products. Cowering in fear on the bathroom floor, Carrie’s humiliation and confusion (her mother has never explained menstruation to her) help form the catalyst allowing her to unleash her devastating telekinetic powers. King links the onset of menstruation with Carrie’s outpouring of pent-up rage. Drenched in pig’s blood on her prom night when her classmates attempt to embarrass and belittle her, Carrie’s traumatic passage into womanhood allows her the opportunity to find and unleash her true potential — to destroy all those who would seek to destroy her. No longer a child, nor an impotent victim, she uses her new-found fertile femininity as a deadly weapon of revenge.

Similar stakes are at play in the 2000’s Canadian werewolf horror movie “Ginger Snaps” directed by John Fawcett. Ginger Fitzgerald, a self-styled gothic outsider fascinated with suicide and death, is attacked by a lycanthrope monster, the “Beast of Bailey Downs,” almost at the exact same moment that she experiences menarche. Thus, menstruation and her “monthly change” are unavoidably linked. Ginger grows hair in awkward places, and even starts manifesting a tail. Her behaviour grows inevitably more monstrous and violent, which her sister, Brigitte, points out with alarm. Ginger denies such changes, attributing any differences in her behaviour to normal hormonal reactions.

I’ve got hormones,” she says to Brigitte when confronted. “And they may make me butt-ugly, but they don’t make me a monster.”

Previously uninterested in any of the males at her school, post-bite Ginger is suddenly sexually insatiable, going so far as to engage in risky, unprotected sexual intercourse and infecting her clueless partner. It is implied that although he instigates their initial sexual contact, ultimately she rapes him as she asserts her sexual dominance.

“I get this ache,” Ginger tells her sister later. “I thought it was for sex, but it’s to tear everything to fucking pieces!”

While we might assume that these urges are the result of being bitten, they are also tied to her new-found awareness of her physical body and her burgeoning womanhood. Femininity as a weapon once again.

Typically, as is often the fate of female characters in horror, both Carrie and Ginger meet untimely ends. Their powers are so immense that they become unstable, driven by revenge or desire. It’s a narrative we are told repeatedly in fiction and real life: “That time of the month makes women go crazy.” They are irrational, dangerous, and unhinged. Just like a beast or monster, you cannot reason with them.

King would later revisit the idea of menstruation heralding Very Bad Things in his subsequent novels, “IT” (1986) and “The Tommyknockers” (1987). In “IT” Beverley’s fear is that of transitioning from childhood to adulthood, and the arrival of her period punctuates this. With her mother deceased, and no female figure of authority in her life, she is clueless about her changing body. Similarly, her physically abusive father now sees her maturing form as an invitation to sexually molest her.

In “Tommyknockers,” Bobbi Gardener begins menstruating so heavily, her repulsed lover wonders if she will need a transfusion to replace the loss. This overly heavy flow is in response to her digging out an alien spaceship, buried for aeons in rural Maine. Her hair and teeth start falling out, and she turns translucent, finally undergoing a metamorphosis where she resembles the blob-like aliens themselves. Is this perhaps some clumsy metaphor showing how menstruation equals youthfulness and fertility, and when it halts, menopause will (allegedly) steal a woman’s youth and beauty? Sadly, King’s writing at this time was much too sloppy for us to be sure.

In many societies, menstruating women are shunned or vilified for being unclean or even sinful. Bleeding women may be banned from places of worship, or excused from performing prayers. Certain religions may prohibit the woman from preparing food for others, or engaging in intercourse.

Conversely, in some historic cultures, menstruating women were seen as powerful and sacred beings; formidable warriors much stronger than men. In pre-colonial Māori communities, for example, menstruation was seen as an honour that represented a oneness with life-flow. A young girl’s menarche was celebrated with rituals and seen as a rite of passage.

Anne Rice uses the notion that menstrual blood might bring strength when she offers it up as an unusual meal for the vampire Lestat, in the fifth book of her Vampire Chronicles series, “Memnoch the Devil” (2000). In an act which some readers thought controversial, and others considered utterly abhorrent, Lestat drinks the menstrual blood of the devoutly Christian Dora so that he may gain necessary sustenance from her blood without hurting the woman. The scene is sometimes referred to, tongue-in-cheek, as “a vampire period drama.” Whatever Rice’s reasons for including this act it does, albeit briefly, suggest the idea that rather than being a dirty, waste product, menstrual discharge could be both nutritious and revitalising. That women could both derive and share power from their bleed.

Not a horror text, but a fantasy series, Alison Croggon’s “Pellinor” books also equate menstruation with power. In “The Gift” (2003) every significant event occurs when the central character Maerad experiences her period. She realises the connection between blood and strength and discovers how powerful she is. This heralds Maerad’s awakening, and understanding of what it means to be a woman. Menstruation signifies a sense of becoming, of maturing and finding strength in herself.

Menstrual blood might indeed be powerful, and life-giving, but in horror, there is very often a dark twist. “The Murders of Molly Southbourne” (2017) is horror novella by Tade Thompson which focuses on the life of the titular character. Molly suffers from an unusual condition; every time she bleeds, a doppelgänger grows from her blood. Within three days, the doppelgänger “goes bad” and attempts to kill her. In order to survive, she is forced to kill “herself.” Her situation is somewhat complicated by the onset of puberty and subsequent menstruation, with doppelgängers arriving with every cycle. Thompson’s story is an intriguing, and often violent, allegorical look at what it means to grow up female, and offers an interesting connection between puberty and mental illness — a time when many sufferers may first see their symptoms manifest. Molly’s blood brings life, of a fashion, but it is not good life.

That blood is life is both a philosophical and biological notion: to lose blood from a wound or other orifice usually indicates trauma and possible death. Blood loss from an area which is seen as inherently sexual, and is not in response to trauma or harm, suggests a transcendence from usual biological rules. These bodies are so powerful they can slew the lining of their wombs each month, and be ready to nurture new life inside them a mere two weeks later. A cycle of death and life with each new moon.

Menstruation in horror fiction is frequently used to signify that terrible “Otherness” which the genre seeks to invoke. Either by amplifying the belief that it is sinful or unclean, or as a harbinger of immeasurable and uncontrollable feminine power. As a great deal of horror fiction is often skewed towards men, both as creators and consumers of, what could be more Other than this unrepentant cycle, one over which they have no control? Representation differs between the genders, with female writers offering an (unsurprisingly) more realistic and pragmatic view of “lady time,” while men frequently equate being “on the rag” as an indicator of unexpected violent outbursts or uncontrollable sexual energy — sometimes even both.

In addition to books and film, some examples of menstruation can also be found in horror video game narratives. However, with such games being marketed primarily at male players, menstruation, yet again, most often signifies the monstrous Other. In “Bioshock Infinite”, it is Elizabeth’s menarche at age 13 which incites a spike in power readings on the massive machine, The Siphon. To reach her full potential, however, requires blood, and it is blood which Elizabeth says highlights the difference between a girl and a woman.

In Telltale Games’ “The Walking Dead” even a zombie outbreak can’t stop the onset of puberty, with the motherless Clementine experiencing her first bleed and feeling bewilderment and fear at having no idea what it means. It is up to group leader Javier to do his best to explain it to her; a duty which many men, mostly due to societal conditioning, might indeed find “horrific”.

Menstruation might well be the Last Taboo, and its inclusion in horror fiction is often problematic or dangerously destructive, but unlike in horror, science fiction and fantasy writers do not seem as squeamish about adding menstruation into the mix. Corrine Willis’ short story “Even The Queen” (1992) explores how women who no longer need to endure a monthly bleed due to scientific and medical breakthroughs, opt to experience it by choice, even going so far as to call themselves “Cyclists”. It has been described as a sly and subversive jab at feminism, but also imagines a future where women might have more autonomy over their bodily functions. It notes very clearly the negative aspects of an unwanted bleed, and how much freedom can be regained when it’s no longer necessary. While the young daughter praises the supposed miracle of womanhood, her mother knows much better — that menstruation also brings with it pain, mood changes and a literal bloody mess.

End-of-the-world novels very rarely feature a female protagonist. Stories by Octavia Butler, P.D. James, and Margaret Atwood are some of the few who buck the trend. Add to this list Meg Elison’s “The Book of the Unnamed Midwife” (2014), a post-apocalyptic exploration of how men and women’s experiences of a broken world can differ greatly, especially in times of societal crisis. The book is written primarily in journal format, and follows a female medical worker struggling to help and provide medical care to the women she meets on her journey to find civilisation. Women are scarce in this future, with large numbers killed off by an unknown plague which also makes childbirth deadly. Added to that, most women are raped and enslaved by the remaining men — the protagonist even poses as male to evade capture. Menstruation, pregnancy and sexual assault are all examined in honest detail. This is a violent and harrowing tale which never shies away from the more visceral, bloody parts of being a fertile woman, but also examines their strength and resilience.

Fiction has no shortage of female characters adopting a masculine appearance as a form of defensive camouflage, but David Twohy’s horror sci-fi movie “Pitch Black” (2000) adds menstruation and gender-stereotyping to the mix. While the crew members assume Jack is a boy due to her choice of clothing and hairstyle, she is outed — without her consent — as female by the prisoner Riddick.

“I thought it’d be better if people took me for a guy,” she says. “I thought they might leave me alone instead of always messing with me.”

It’s a powerful statement which offers a scathing commentary of a patriarchal world where girls who have entered puberty may suddenly be seen as sexual objects of desire. An understanding that menarche opens a door not only to womanhood, but also to danger.

Ultimately, despite the suggestion that her monthly bleed may put a kink in the crew’s plan to avoid the deadly creatures that are hunting them, and escape the alien planet, Jack proves to be a strong and capable survivor. Dealing with menstruation while running for your life may be an inconvenience, but it certainly does not indicate weakness.

To conclude, I want to mention the more upbeat (but still deliciously dark) short story “Logistics” (2018) by A.J. Fitzwater. Another post-apocalyptic speculative-fiction tale, this is a first-person account of Enfys and their search for sanitary products at the end of the world. It is as much an exploration of gender as it is the issues and physical trials of menstruation, but acts as a thoughtful reminder that biology does not equate to gender, and the two are sometimes in conflict. Likewise, simply being in possession of a working uterus — whether you want one or not — brings its own unique challenges. “The monthlies” don’t just stop because civilisation is in pieces.

Examples of menstruation in darker genres clearly emphasise the shame, myths and frequent inconveniences that surround it, but they also illuminate, in ways that are often uncommon in fiction, the conflicting emotions felt by menstruating women about their bodies, and of those around them. As well as exploring the societal fear that the menstruating woman is a threat, these stories also show her powerful side, her resilience and sexual strength. The menstruating woman celebrated as a warrior and survivor, not as a monster to be feared.

Other examples of menstruation in horror & dark fiction:

“Wolf-Alice,” short story from The Bloody Chamber, Angela Carter (1979)

“The Handmaid’s Tale” Margaret Atwood (1985)

“The Crossing” Mandy Hagar (2009)

“Shiftless” Aimee Easterling (2014)

“Man-Eaters” (graphic novel) Chelsey Cain (2018)

The Witch, dir. Robert Eggars (2015)

Jennifer’s Body, dir. Karyn Kusama (2009)

It Stains the Sands Red, dir. Colin Minihan (2016)

A Tale of Two Sisters, dir. Jee-woon Kim (2003)

Excision, dir. Richard Bates, Jr (2012)

Teeth, dir. Mitchell Lichtenstein (2007)

Buffy the Vampire Slayer, dir. Fran Rubel Kuzui (1992)

Non-fiction:

“Women, Monstrosity and Horror Film: Gynaehorror” Erin Harrington (2018)

“The Vagina as a Bleeding Wound: Monstrous Puberty in Carrie, The Exorcist and Ginger Snaps” Kate Maher

“Writing Horror and the Body: The Fiction of Stephen King, Clive Barker, and Anne Rice” Linda Badley (1996)

“Misfit Sisters: Screen Horror as Female Rites of Passage” Williams, Christy, Marvels & Tales (2006)

Read online:

“Even The Queen” Corrine Willis

http://www.e-reading.club/bookreader.php/71143/Willis_-_Even_the_Queen.html

“Logistics” A.J. Fitzwater

Tabatha Wood

Author

She released her debut collection, “Dark Winds Over Wellington: Chilling Tales of the Weird & the Strange” in March 2019. Since then, she has been published in two “Things In The Well” anthologies, plus Midnight Echo and Breach magazines.

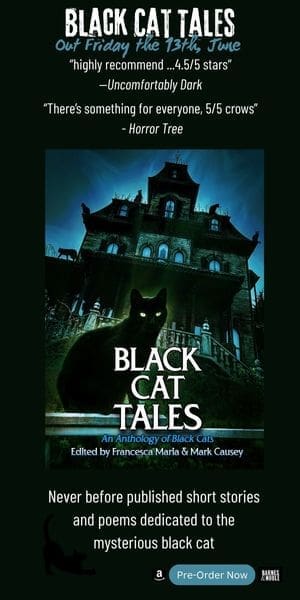

Tabatha is currently working as the lead editor for upcoming charity anthology, “Black Dogs, Black Tales,” which aims to raise money and awareness for the Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand.

You can read stories and articles on her blog at https://tabathawood.com and keep up to date with her upcoming projects via Facebook https://www.facebook.com/tlwood.wordweaver/

What a fab post. I have included periods as a major part of one of my short stories. I have not yet heard back from the editor, but hopefully it won’t be deemed too icky.

Hi, Tabatha. I enjoyed your rundown of some depictions of menstruation in horror. You left out Theodore Sturgis’ Some of Your Blood, about a vampire–well before Rice! And if we’re including the more “horror” elements of a romance novel, Edward in Twilight wasn’t interested in Bella’s period because it was “dead blood,” or something (I’ve read about it, haven’t read the books).

That said, you made a mistake about the novel version of IT. In the novel, Bev’s mother is very much alive, though she works all day and pretty much leaves Bev to her own devices. While Bev is starting to develop, there’s no mention of her period yet, and the sexual abuse element in the 1958 scenes is much less obvious than in the film. She writes that it’s as if she and her father create a “smell” between them. As the summer wears on, IT takes over her father and it gets worse.

All the menstruation stuff you talk about here, as well as Bev’s mother having passed away, is in the film version. In the book blood comes out of the drain, but it’s less tied to Bev’s period than in the film.

In your assessment of the film’s relationship to her period (and callback to Carrie), I think you’re correct.

There is another bit about periods in the book version of IT, in the first section where we “meet” Patty, Stan Uris’ wife. She and Stan have trouble conceiving, and there’s a bit where Patty imagines her tampons and pads saying something like “We’re your children. Nurse us with blood.”

How different than some other depictions of menstruation. I remember a late season episode (I think the last or next to last season) of The Cosby Show. Rudy starts her period, and Claire takes her out for “Woman Day,” which she does for each of her daughters. It’s a celebration, not a shame.

Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting’s female characters pretty much are about their periods. One gets her period. One is close to 50 and proud that she still has her period (menopause is another sort of horror). Signs of a writer who really doesn’t know how to write his female characters.

Menopause, of course, is an entirely different subject. Note how many villains are middle-aged women. Nothing is scarier than that!