Epeolatry Book Review: The Merry Spinster: Tales of Everyday Horror by Daniel Mallory Ortberg

Disclosure:

Our reviews may contain affiliate links. If you purchase something through the links in this article we may receive a small commission or referral fee. This happens without any additional cost to you.

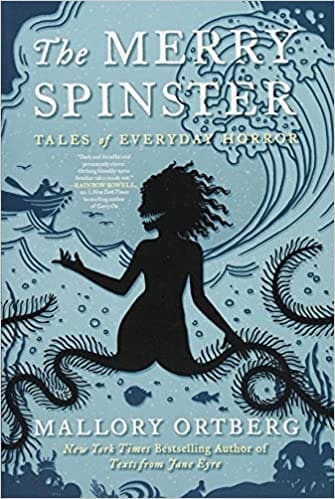

Title: The Merry Spinster: Tales of Everyday Horror

Author: Daniel Mallory Ortberg

Genre: Horror

Publisher: Corsair

Release Date: 13th March 2018

Synopsis: From Mallory Ortberg comes a collection of darkly mischievous stories based on classic fairy tales. Adapted from the beloved “Children’s Stories Made Horrific” series, “The Merry Spinster” takes up the trademark wit that endeared Ortberg to readers of both The Toast and the best-selling debut Texts From Jane Eyre. The feature has become among the most popular on the site, with each entry bringing in tens of thousands of views, as the stories proved a perfect vehicle for Ortberg’s eye for deconstruction and destabilization. Sinister and inviting, familiar and alien all at the same time, The Merry Spinster updates traditional children’s stories and fairy tales with elements of psychological horror, emotional clarity, and a keen sense of feminist mischief.

Readers of The Toast will instantly recognize Ortberg’s boisterous good humor and uber-nerd swagger: those new to Ortberg’s oeuvre will delight in this collection’s unique spin on fiction, where something a bit mischievous and unsettling is always at work just beneath the surface.

Unfalteringly faithful to its beloved source material, The Merry Spinster also illuminates the unsuspected, and frequently, alarming emotional complexities at play in the stories we tell ourselves, and each other, as we tuck ourselves in for the night.

Some authors seem destined to shake things up in the best way possible. Daniel Mallory Ortberg is a New York Times bestselling author. Courtesy of his debut work Texts from Jane Eyre, which was based upon his longstanding columns in “The Hairpin” and “The Toast”, it envisions famous literary characters exchanging anachronistic text messages. A trans man who transitioned in 2018 and took his wife’s surname when they married a year later, The Merry Spinster is his second work.

The Merry Spinster is a slender anthology of short fiction. It retells classic fairy stories like “The Six Swans” by the Brothers Grimm, and folk legends such as the Orkney folktale “Johnny Croy and His Mermaid Bride”.

“The Daughter Cells” is a retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid”, and it explores the soul of the natural world as a multifaceted entity reflecting Nature’s complex interconnectedness. The human desire to own and control, and of course our inherent selfishness, are set in stark contrast to the world below the waves.

“The Merry Spinster” (recasting “Beauty and the Beast”) exhibits a profound ambivalence towards marriage as the sole narrative drive of the heroine, especially when the man concerned is so challenging. Toxic masculinity can be tamed by the love of a good woman, to be sure, but why is the woman having to do all the emotional work, Ortberg asks.

Recasting fairy tales and folk legends for a modern audience, or simply retelling them in a way that is more empowering for women and other minorities, is fertile territory for horror writers. This is true at the literary end of the spectrum, as with this volume, and towards the more popular end of the fiction market. In a process brought to worldwide attention by Angela Carter in the early 1990s when Virago published two books of fairy tales which she edited, writers have been reclaiming fairy tales and folk legends as their own. They’ve wrestled them from the likes of the Brothers Grimm and Walt Disney ever since.

The best writers give something of themselves in their work, however discreetly this is achieved. One of the things I love most about Ortberg is how true this is of his writing. Educated at the private Azusa Pacific University and raised by Evangelical Christian parents, it isn’t surprising that faith is explored extensively within these pages. The ‘Sources and Influences’ section at the page lists, among others, “The Ladder of Divine Ascent” by St John Climacus and “Summa Theologica” by Thomas Aquinas.

Gender issues were also in play, with a thoughtful and potentially personal retelling of “The Frog Prince” by the Brothers Grimm. Here the youngest daughter takes the role of princess in the title (“The Frog’s Princess”) but is referred to as ‘he’ throughout in a way that felt compellingly natural to this non-binary reviewer.

This was an immensely subtle but thought-provoking anthology. After two slow reads through for the purpose of this review, I feel like I’m only beginning to scratch the surface of what it has to offer.

Review the reviewers! If you’ve read this novel, or just have some thoughts on any point made in this review, tag me at @JohnCAdamsSF on Twitter to share them.

5/5 stars