‘Skin’ Blog Tour – The Body in Fear

The Body in Fear

By Kathe Koja

If you write things that cause fear, you know how to describe the deliberately unseen, know how to go where the rational deserts us, and no one will help us, and flight or violence might be our only options for survival: you know what it feels like to be afraid.

But then the day’s work is over, and you leave that fearful place behind.

Unless you can’t. Unless you find yourself living in ongoing peril, find yourself hunted, politically targeted, find yourself in a time where there seems to be no safety at all. You have some options then: confront the threatening reality, pretend it’s not happening, or collaborate with it. But whatever option you choose, your body will have to deal with the fear.

The average duration of a movie jump scare is five seconds, time enough to gasp, recoil, then laugh; it’s a mini rollercoaster ride for your body, it’s the startle response. (As humans, we share that with many other mammals, amphibians, and birds.) Our eyes widen, our muscles prepare for assault, adrenaline hits the bloodstream—we can’t turn this off, or prevent it, it’s part of what we are—and then the scare ends. Our bodies stay alert awhile longer, though, just in case.

But daily fear is a much different situation. It may ebb, it may boil, but it never ends, there’s never the moment when we say “Whew!” then feel it pass; it lives in us, like a coiled weapon, like a sickness, like a strain we carry without consent. Shoulders tight, gastric system troubled, heartrate increased, cortisol teaching the body lessons it should not learn, always focused outward, separated from ourselves in a fundamental way, that’s what we become, in daily fear. And the exhaustion of dread, the rage that’s bred by oppression, the loss of sane focus, all these can be present too.

Body horror may be the literature best suited to explore this landscape: body horror is already adept at understanding the power fear holds, and how vulnerable the flesh is, and the mind inside it. To describe something is to help to have, if not control over it, then understanding of our own footing, our own chances for survival, within it. And that makes for powerful work. And useful work, too. Because we are our bodies, every day we breathe.

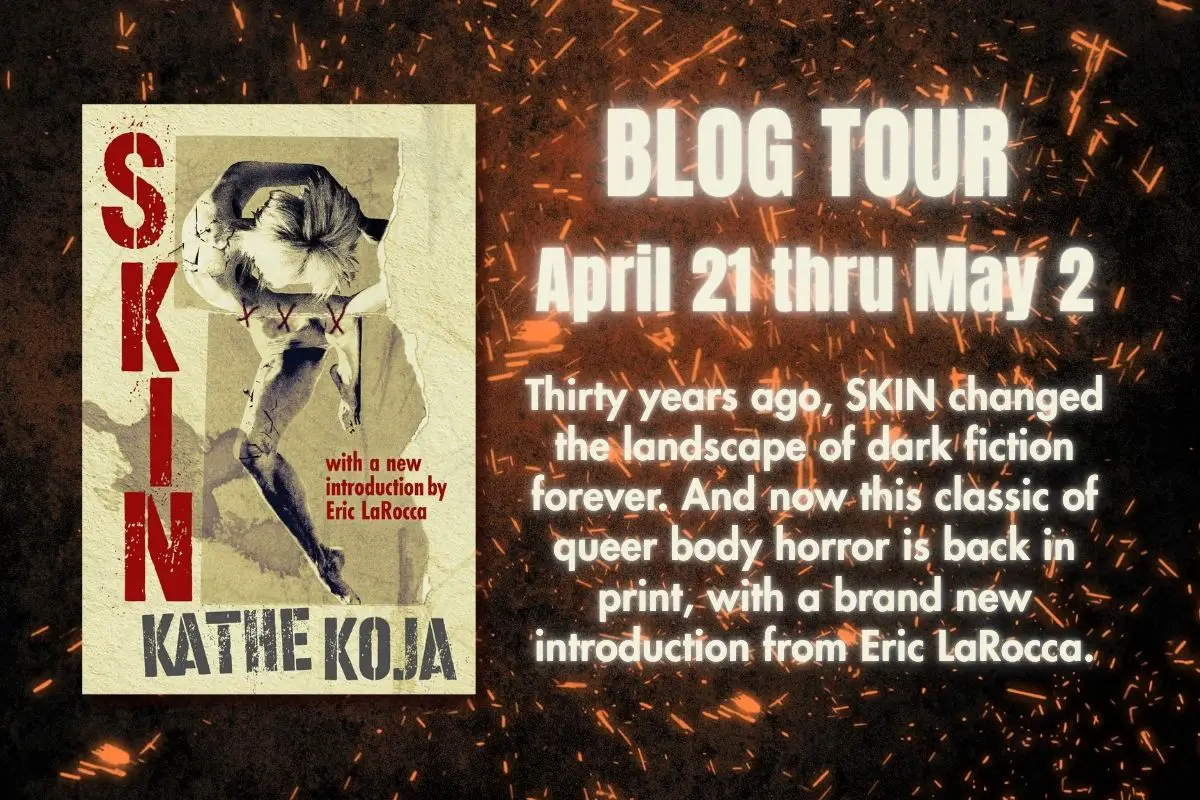

SKIN by Kathe Koja

SKIN by Kathe Koja

With a new intro by Eric LaRocca

RELEASE DATE: April 22, 2025

GENRE: Horror / LGBTQ

BOOK PAGE: Skin – Meerkat Press

SUMMARY:

Thirty years ago, SKIN changed the landscape of dark fiction forever. And now this classic of queer body horror is back in print, with a brand new introduction from Eric LaRocca

Tess burns. Bibi cuts. Together they create chaos, love, pain, and unstoppable art, in SKIN, the story of a partnership that sparks like flying metal and bleeds like a breaking heart.

BUY LINKS: Meerkat Press | Bookshop.org | Amazon

GIVEAWAY: $25 Meerkat Press Giftcard

GIVEAWAY LINK: https://www.rafflecopter.com/

EXCERPT

Crane was six feet tall and all in black, steel-rimmed glasses with tinted lenses round as the little juice bottles she bought downstairs. He started talking as soon as the door opened and worse yet had not come alone: a woman with him, behind him, hanging a little back in the hall but not shy; waiting. Waiting, Tess saw, for her and not Crane to say it was okay.

“Come on in,” she said, and the woman stepped forward, past Crane; not quite as tall as him, not quite as tall as Tess: younger but more muscled, athlete’s legs, or dancer’s, smooth bare skin like Teflon over steel. Her handshake was very strong but she did not squeeze the way a man might.

“I’m Bibi Bloss,” she said.

Foxface bones, pale bright hair and eyes the same: incandescent, less broken glass than the sheer act of breaking. When she smiled Tess saw her teeth were very small, milk teeth, strange childish grin.

“You do all your own welding, don’t you?” Crane was looking around the room, moving to the pieces she had pushed in a corner, sculpture forestry about his legs and waist. “This one’s kind of interesting,” he said, careless hand above the razored ribs of Mater Intrinsecus, fierce her crown of sheared bearings and Tess pushed his hand brusquely away.

“That’s really sharp,” she said. “Listen, why don’t you tell me what you need.”

“Fine,” he said. “I don’t even know if you can help me at all. What I need primarily,” and Bibi now to where the toilet was, the green wall of the shower, moving as if through a particular silence of which no one but she was aware, “is information. I have a special piece in mind,” and off on some weird impossible tangent, he worked with aluminum, he should know better. Maybe he didn’t. She tried to explain why there was no doing what he wanted to do but he wasn’t listening, he was talking about layers of metal mimicking layers of meaning, talking about metallurgy as metaphor and the intrinsic barbarism of iron in such a way that she felt like striking an arc off his steel-rimmed glasses; and looking past him to see Bibi beside another piece, Dolores Regina and her fingers loose and deft on half-deliberate spatter, the flat fillet weld, streetlight from behind less halo than warning light and chicken-wire shadows on her face like the solemn etching of tattoo. Standing there she was sculpture, strong iron bones and solder muscles, the tilt of her head a construct so subtle that Tess stared, the flat appraising stare of the scrapyard as with the grace of gears meeting Bibi’s head turned, to watch Tess watching her.

Crane just noise in the background now and Bibi’s gaze calm and calmly thorough, Tess and the room and the sculpture both harbored, everything plain to those eyes. Tess still as metal in her own silence and Crane finishing up, so what did she think? How long would it take to do?

Shaking her head, can’t be done and his irritation immediate, “Why not? It seems easy enough to me.”

Then go do it, asshole. “Look, all I can tell you is I can’t do it. All right?”

“Well, then,” a busy man in pursuit of his art, “can you recommend anybody? I have to get—”

From across the room, still in that posture: “Tess. Why haven’t I seen your stuff before?”

Glance down, reluctant now to meet those eyes straight on. “I don’t show much.”

“Why not?” Nodding inclusion, the sculpture, the worktable. “It’s brilliant work. Don’t you have an agent or anything? Are you represented by a gallery?”

Tess’s smile involuntary, and Crane again, excluded and annoyed, “She’s showing right now at the Isis,” and again Bibi ignored him, or rather accepted the information as if it had dropped like a pearl from the bodiless air: “The Isis? You don’t belong there.”

“I don’t belong anywhere,” and wondering as she said it why she had, it sounded so sophomoric, so moronically proud. “I just, I don’t really show much.”

“Listen,” Crane louder, dragging back attention, one hand full of keys impatient, “can you help me or not?”

“No. I can’t.”

Before his answer, Bibi’s smile: “Thanks,” as if it had been on her errand they had come. “I’ll see you.” And gone that moment, out the door and Crane pausing to watch as she did Bibi’s silhouette, one long-stepping muscle in tension and his irony, “Well thanks,” and graceless down the stairs. Tess watched for a moment longer, to see if she would come back. Nothing. Closing the door, slowly, strange strange eyes and then forgetting it all in the turn and step, back to the workspace and taking up her mask, flipping the grounded switch to start the final burn.

—

Sleeping in to wake sweaty and muscle-sore; the piece was done. Scrap steel and Lexan, glass and the warped plastic throat, it was better than she had expected though still not where she wanted to be; where was that? who knew? She would know when she got there. Still the piece was good: textures all a-mesh and it almost seemed to move, to twitch when not watched, calm semblance of silence in the moment of attention. Smiling a little to think of it creeping loose around the room, trying the windows, trying the door, peering eyeless to clear its plastic throat; dry in self-mockery: anthropomorphizing; watch it. She knew people, artists, who liked to gurgle about their “babies,” their “children”: “Every one of my pieces is a child of mine,” who had said that to her? Horseshit. Children were children and work was work and people were assholes when they started believing their own arty bullshit. They should all work with metal, get burned once in a while: keep them grounded.

In the shower, the last of the soap in her eyes and somebody knocking, not banging but hard, Tess heard it plainly over the water. Determined. “Shit,” hissed between her teeth, eyes burning. Loud: “Who is it?”

Indistinct.

“Who is it!”

“Bibi Bloss.”

Dripping on a T-shirt, the towel around her head, shooting back the dead bolt: “Come on in.”

Alone, smile and ripped leggings, slipping off her black sunglasses to hook them in the stretched neck of her T-shirt. “Hi,” closing the door. “If this isn’t a good time, please say so.”

“No, it’s okay.” Stringy wet bangs, dripping onto her cheekbones. Crane’s errand? or her own?

Unerring toward the worktable, she had little feet, Bibi, bony ankles above disintegrating sneakers, she cocked her head like a listening animal and said nothing at all. Examining the new piece for literal minutes, a long time to stand staring but her eyes were busy as a bird’s, she left nothing out. Finally: “It’s ready to move, isn’t it,” not a question and Tess nodded, pleased with more than the pleasure of surprise.

Glancing at the metal rack, tools still in last night’s orderly scatter; sun through the chicken wire, endless burn holes and dust. “Tess. Why do you live here?”

Surprised, “It’s cheap. Why?”

“I just wondered.” There was definitely more to it than that but no more was coming now. Silence; Bibi’s dirty finger on the piece’s throat.

“What?” wiping at her wet neck, water in her eyes. She felt no footing here, was unsure what to say until she did. Bibi saw, or seemed to; seemed to understand because she nodded, once and brisk.

“I know; what do I want. Listen, today I made a pilgrimage to that creepy Isis Gallery. —Without Crane, incidentally, who’s back at his place with two other guys trying to figure out what you told him last night.”

“Doesn’t he do his own welding?”

“Crane doesn’t know shit about welding. Why else do you think he came to you?” A pause. “I’m glad I came with him.”

It sounded rude; she said it anyway. “Why?”

“Because of your work.” Full stare, her eyes washed marble light and fingers unconscious on the piece before her. “I wanted to talk to you last night, but not in front of Crane. You must have noticed he’s a size-eleven asshole, once he gets started you can’t shut him up. And besides, it’s none of his business.”

“Are you, is he your—’

“I used to live with him, if that’s what you’re asking. He’s part-time in a dance group I’m in—he’s a much better dancer than he is a sculptor. Which still isn’t saying a whole hell of a lot,” and that strange little grin again, dry as the curve of a bone. “No, what’s mostly wrong with Crane is that he doesn’t have anything I want.”

Tess smiled, as much in surprise as discomfort; at least she was honest. “Do I?”

“Yes. I want to see all your stuff.”

“Why?”

“Show me,” shark’s grin, “and I’ll tell you.”

She ended up showing everything, all the way back to Mother of Sorrows, the oldest piece she still had. Beginner’s work, not even good enough to be called crude but Bibi inspected it as she did all the others, attention severe and severely focused, all of her there in her eyes. Hot crouch in the endless turn of the fan, windows empty of any breeze and both of them sweaty, spotted with the floating grime from moving between pieces, moving the pieces themselves. Some were painfully heavy, but Bibi was strong as she looked, and stronger; she held up her end with ease. The afternoon passing in a running catalog of material, place, title, then on to method and juice drunk standing, cookies eaten crumbling from the box. The theory and practice of welding, her own experiences, dreary and not, keno accompaniment a chatter and grind to the rod-tip-in-the-shoe story and Bibi’s shut-eyed laugh, really funny.

More talk, Bibi’s questions and they were good ones, ancient to modern history now and asking why this place, why not more shows; why the Isis? One dirty hand light on the swollen iron back of Lay Figure, its hideous humps like bones distorted, the face one howling O of blackened wire: “And this is one of the pieces you were going to show there?”

“That, and Delta of Silver,” nodding to the riverine figure of solder and charred iron bone, melancholy line of shine beneath the overhead fluorescents. Night coming on and this day gone purely in talk, when had she done that last? Past memory, loner weeks and months, plenty to do; still did; always did. But no one to talk about it with since, what? All the way back to Peter? Sweet ugly Peter, last lover, almost-best friend with his found sculpture, plastic milk jugs and detergent bottles, and sidewalk paintings that took him finally where it was warmer, where, he said, the sidewalks stayed dry all year. Two letters, one long awkward phone call, already long gone but she was stubborn, she had to be hurt hard to let go. He ended by obliging her, poor Peter, she had not meant to cause such pain to either of them; he was not a monster, he did not want to wound her so. What would he think of her work now? What would he think of her? Strange to think of Peter, now; she had not in so long.

A sigh, and back all at once to Bibi’s quizzical gaze, there was something she should be saying, explaining. The Isis show, right, the pieces they wanted and didn’t want. “They only took one,” sitting up straighter. “The one you saw, Archangel.”

Impossible to read those eyes, washed to nothing but light. “Why didn’t you show them all?”

“They didn’t want them all.” The painstaking slides rejected, half an explanation half a month late but she had not wasted time with anger, she had been through this before. Leaning on the toilet wall, pinch of green plastic against her sweaty back. “You were there, you saw what they show. They don’t want stuff like mine, that’s not what they’re interested in.”

The exposed tines of Lay Figure’s bones denting the bare skin of Bibi’s arm, she did not seem to feel or notice. “What are you interested in?”

“Metal.”

At once, like a teacher, a cop: “What else?”

“Making it . . . work.” Her hand moving in half a circle: frustration’s symbol, the answer incomplete. “Making it do what I want.”

“What do you want?”

“I don’t know,” flat and honest, out before she could think or rethink to call it back. “I guess I’ll know it when I see it. If I see it.”

“You won’t. Unless you build it yourself.” And trapdoor sudden, little meat-eating grin and “Hey: come on. Come see what I do, now,” keys without looking, open door and on the landing to stop: and wait for Tess.

Who stood, waiting herself. “You never said,” scarred hand poised on the light switch, the light from the stairway a greasy yellow, cloudy with the tiny blunderings of flies trapped by false eternal daylight, around and around. Downstairs the sounds of big kids yelling, the dumpy thump of a loaded handcart over the uneven threshold.

“Said what?”

Hitting the switch, sudden black and Bibi clear, then shadowed as she moved closer, half-back across the threshold. “What you want.” Want to give. Or share. Or take.

Very close in the dark, one hand on the jamb and a smell to Tess like sugar, like sweat, distinct and oddly nameless, your own secret scent found inexplicable on the flesh of another. Her eyes could have been marbles, or bearings, or Lexan chipped cold with scavenged glass, eyes that wait and see in any dark, the eyes of sculpture ready to move when no one watches, ready to crawl and buck and scratch slow paint from the shivering walls like skin from the shrinking lines of tender bone.

“I don’t think I need to tell you,” Bibi said. Voices up the stairwell, the jitter of empty bottles like tumbling coins, somebody’s curse and her closeness, close enough to touch, her stare to Tess as vivid as taste in the mouth. “I really think you already know.”