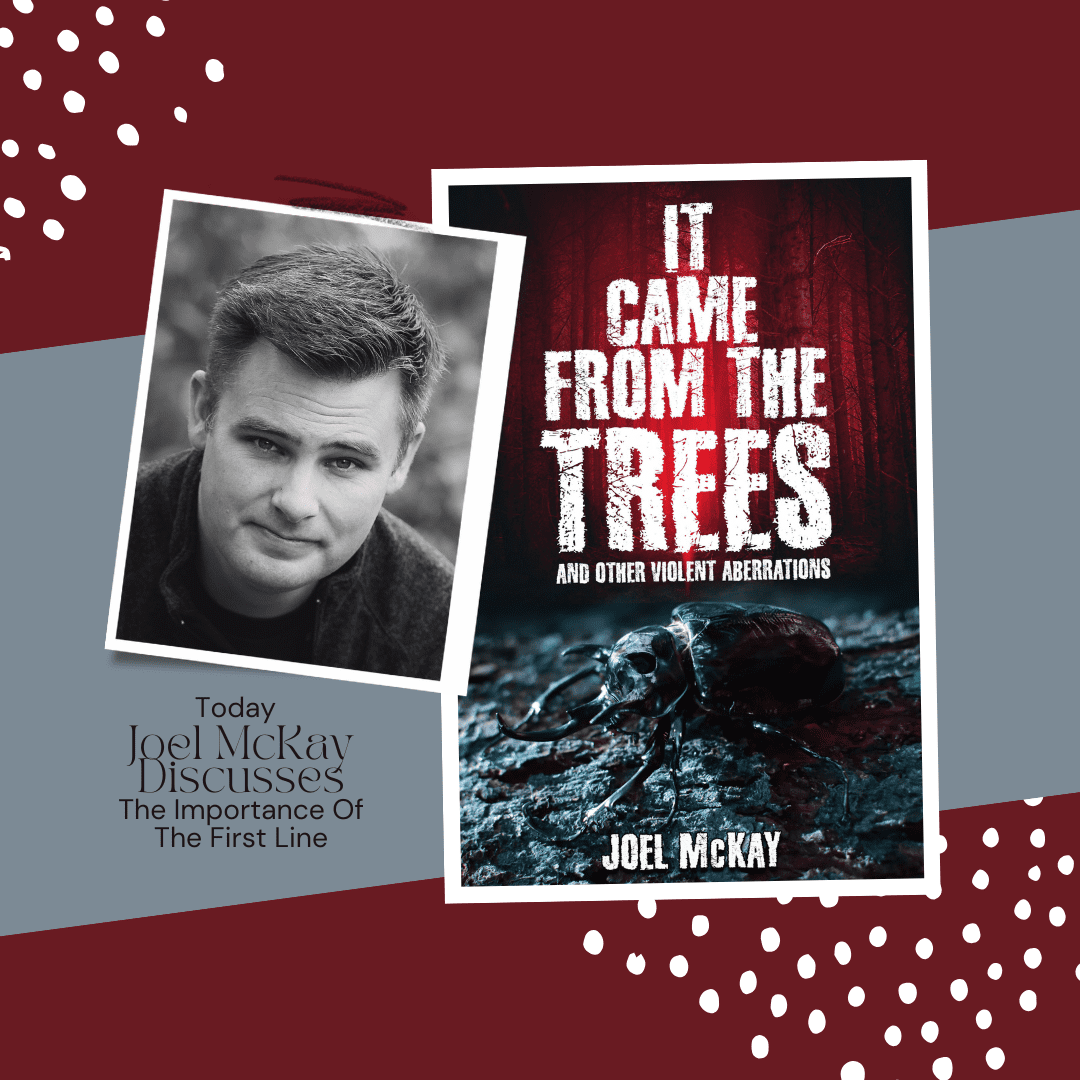

The Importance Of The First Line

The Importance Of The First Line

By Joel McKay

“Jack Torrance thought: Officious little prick.” (King, The Shining, 3).

That’s the first line in, arguably, Stephen King’s most well-known scare fest, 1977’s The Shining.

Terrifying? Not at all.

Engaging? You bet your ass it is, and, more than that, it immediately reveals Jack’s deep-seeded self-confidence issues that manifest as rage, which underpins the entire novel.

So far as first lines go, it’s a stand-out. Let’s review a few more:

“Because he thought that he would have problems taking the child over the border into Canada, he drove south, skirting the cities whenever they came and taking the anonymous freeways which were like a separate country, as travel was itself like a separate country.” (Straub, Ghost Story, 3).

A couple key things I notice here: it is both unsettling and mysterious in that we’re immediately led to think ‘child abduction’, but we’re also now wondering who this is and why.

Second, unlike The Shining, it’s long. And it’s the first line of a 20-page prologue—Straub is easing us in, he’s weaving a story … a story about stories, which, in the tradition of all good ghost stories, require a bit of set up.

Another: “The amber light came on.” (Saramago, Blindness, 1).

Short. Punchy. We see the light, but what is it? A streetlight? A lamplight? Keep reading to find out.

Of course, our ability to see the light is central to this Nobel prize-winning novel of horror, in which an epidemic of blindness is the foundation the book is layered on.

How about Andrew Pyper’s 2013 macabre Dan Brown-esque novel The Demonologist?

“The rows of faces.” (Pyper, The Demonologist, 5).

Or this from Paul Tremblay’s anthology Growing Things: “Their father stayed in his bedroom, door locked, for almost two full days.” (Tremblay, Growing Things, 1).

Here he’s a little more Straub than King, Saramago or Pyper—Tremblay draws us in, gives us a figure with a position of authority and some unsettling behavior.

Pyper, on the other hand, is betting we’re going to read the whole paragraph because we’re not getting much from that first sentence.

Of course, the central question you should ask of all of these is: do you want to keep reading?

My guess is if you got past the cover, the title, the author and through the copyright page, you’ll at least get through the first three to five pages before deciding to carry on.

That’s the best any author can hope for.

So, in fact, your first sentence might not matter so much as that first paragraph or page, especially if it’s short and punchy.

If, however, as a writer you decide to channel Straub or Tremblay, you’re going to want to be a bit more cautious.

I love long first sentences, but I think it better lead somewhere and, if possible, set a tone that draws us in.

A lengthy first sentence of pure explanation is going to be a tough sell.

So, why am I writing about first sentences in horror novels?

A few reasons.

One, just because it’s horror doesn’t mean it needs to scare the pants off you right away (I’m not even sure that’s possible).

Second, short and punchy will draw us in, but, again, it can only take you so far.

You need character, or characters. And those characters need to be after something and then something should get in their way—and there’s your plot, even if it’s only a subplot.

As a writer, I love reading the first sentence of novels.

A lot of time and effort is placed on endings, but I’m a believer that endings matter less than beginnings.

As a reader, I want to be transported into your story, your characters, their situation, as quickly as possible. Get me there. Don’t let me leave or even think about leaving until I’m a ways in.

This can mean that immediate action is helpful, but I prefer a more drawn-out entry point.

As a writer, I often struggle to get a story going unless I have a doorway into it, often just a single sentence or an image.

If I have that correct, I can likely write you a novel, and that first line is unlikely to change in the editing process.

Like a diving board, the first sentence of any story is the jumping off point.

If done correctly, it’s an Olympic dive.

If not, it’s a belly flop.

As readers and writers, I would encourage you all to pay attention to that first line, first paragraph, first page.

What’s happening there?

Revel in it, play in it. Try different things.

Then, carry on.

Or … don’t.

Happy writing.

Sources:

- King, Stephen. The Shining. Anchor Books, 2012.

- Pyper, Andrew. The Demonologist. Simon & Schuster, 2013.

- Saramago, Jose. Blindness. Mariner Books, 1997.

- Straub, Peter. Ghost Story. Berkley, 2016.

- Tremblay, Paul. Growing Things and Other Stories. William Morrow, 2019.