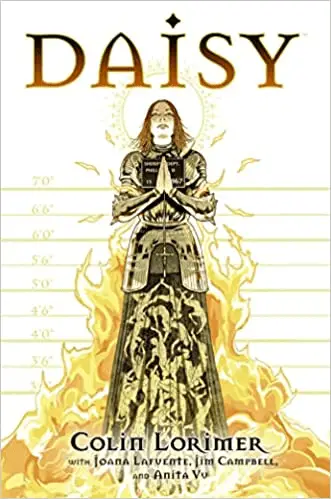

Epeolatry Book Review: Daisy by Colin Lorimer

Disclosure:

Our reviews may contain affiliate links. If you purchase something through the links in this article we may receive a small commission or referral fee. This happens without any additional cost to you.

Title: Daisy

Author: Colin Lorimer (Story and Art) with Joana Lafuente (Colors), Jim Campbell (Lettering) and Anita Vu (Cover colors and additional colors)

Publisher: Dark Horse

Genre: Horror, Fantasy, Graphic Novel

Release Date: 3rd November, 2022

Synopsis: A desperate mother’s search for her missing son leads to the mysterious family of Daisy Phillips. Like many teens, Daisy has a hard time fitting in, but for atypical reasons: Daisy stands over eight feet tall and believes herself descended from cannibalistic giants spawned from the outcasts of Heaven. This frail, disfigured youth may hold the key to unlock the Language of Creation – the divine DNA of God – and expose the monstrous lie hidden within Creation itself.

Lindsay Taylor perseveres in the search for her son, Conor, who went missing five years ago at the age of nine. Following an anonymous tip and with the help of the local sheriff, the pragmatic but hopeful mother finds her way to the dysfunctional family, Phillips. Set aptly in the autumn-winter picturesque Stowe, Vermont, with a brilliant-white church at its aesthetic centre, the comic also deploys fictional locations with names evocative of existing places and their own connotations, such as Brimount, obviously akin to Brimont, a commune in northern France. Cue small-town sensibilities.

Typical only in growing pains and outcast status, teenage Daisy bears all the hallmarks of the lonely outsider, both specifically adolescent and prematurely-aged: braces on legs and teeth, wrist cuffs—one gets the impression she is barely held together—glasses and a cat. The ominous ‘Father’ (referred to as such by the sheriff) has led her to believe that she is the last surviving descendant of the Nephilim, and that she has an integral role to play in rewriting Man’s introduction to corruption and evil. No pressure, then.

Readers are placed among the dour rot of thought and bodies that infuse Lorimer’s comic. You are among visceral, organic nightmares reminiscent of Dante, minus the flamboyant interpersonal jibes. This is a book that takes itself seriously, clutching at the allure of a divine language that could save all, while also sinking its teeth into the ruts of time-old societal traumas. You know, just a light afternoon snack. Lorimer’s artwork itself is accomplished, sketching a dry, dogmatic landscape that you’ll writhe to escape from. Lafuente’s muted, earthy colour palette enhances the theme of decay and transformation, later ascending alongside Daisy into an uncomfortably pleasing grey-gold light.

Despite its indulgent, gore-chomping abjection and the ethereal transgression of life-death boundaries, the real horror of Daisy is domestic. Standard-issue creepy children wear fixed smiles and seem to have accepted death as a neighbour or even a family member. Cult culture pervades in self-preservation via abuse of authority. The central haunting is the refrain of, “For the Greater Good”, a phrase so abused that it is universally horrifying.

An apocalyptic outlier of the Judeo-Christian biblical canon (try saying that five times fast and you’ll feel a sense of the story’s mud-suck heave), the Book of Enoch’s war of angels is here dragged spitting and screaming partway into modernity by means of white-western, small-town horror. But don’t be fooled by the presence of cars and mobile phones. If you like your religious mythology hard-boiled and regressive, rejoice! Women are tools of breeding and patriarchally-puppeted cataclysm, people of colour are few and far between, and disability and deformity are explicit declarations of a corrupted soul.

Lorimer frames the horror of fascism while, eventually, perpetuating the narrative of physical ills denoting sin. During a rise of far-right political rule and a pandemic with lasting impact on the chronically ill and disabled, his timing is complicated, to say the least.

With all benefit of the doubt, I’m sure there’s a point being made somewhere about the toxicity of unchallenged moral-dressed fervour, and the ableist rhetoric at the heart of this particular lore. However, the navel-gazing logic of it is pushed so far through its own sphincter that you’re left wondering what the literal Hell is/has/will happen. Sacrifice, something, something, fresh start? The message misses the mark for me and ends up reinforcing the ‘flood as cure, wipe out and start again’ philosophy. This is for fans of the macabre western gothic, the carnival of horrors, and the voyeuristic penny dreadful.

Content warnings: Ableism, violence, decay (graphic), misogyny (moderate)

![]() /5

/5

- About the Author

- Latest Posts